Why Private Wealth Should Lead Public Investment

America’s Suburban Experiment is an interlude of financial unreality that began at the end of World War II. We are in the process of transitioning out of it, moving to something different. What that development pattern will be is unclear, but emerging constraints suggest that we will learn a lot from understanding the historic relationship between private investment and public investment.

Here is an image I’ve used a lot. It’s Front Street in my hometown of Brainerd, Minnesota:

Front Street. Brainerd, MN, 1870.

Note the amount of public infrastructure serving the little shacks in version 1.0 of this city. There was none. There were no sewer and water systems. No streets or sidewalks. No drainage system. Nothing. The first iteration of the city didn’t produce enough wealth to justify any of those things. The people who built that place had more urgent things to do with their resources than build public infrastructure. They were trying to figure out if this city was going to survive.

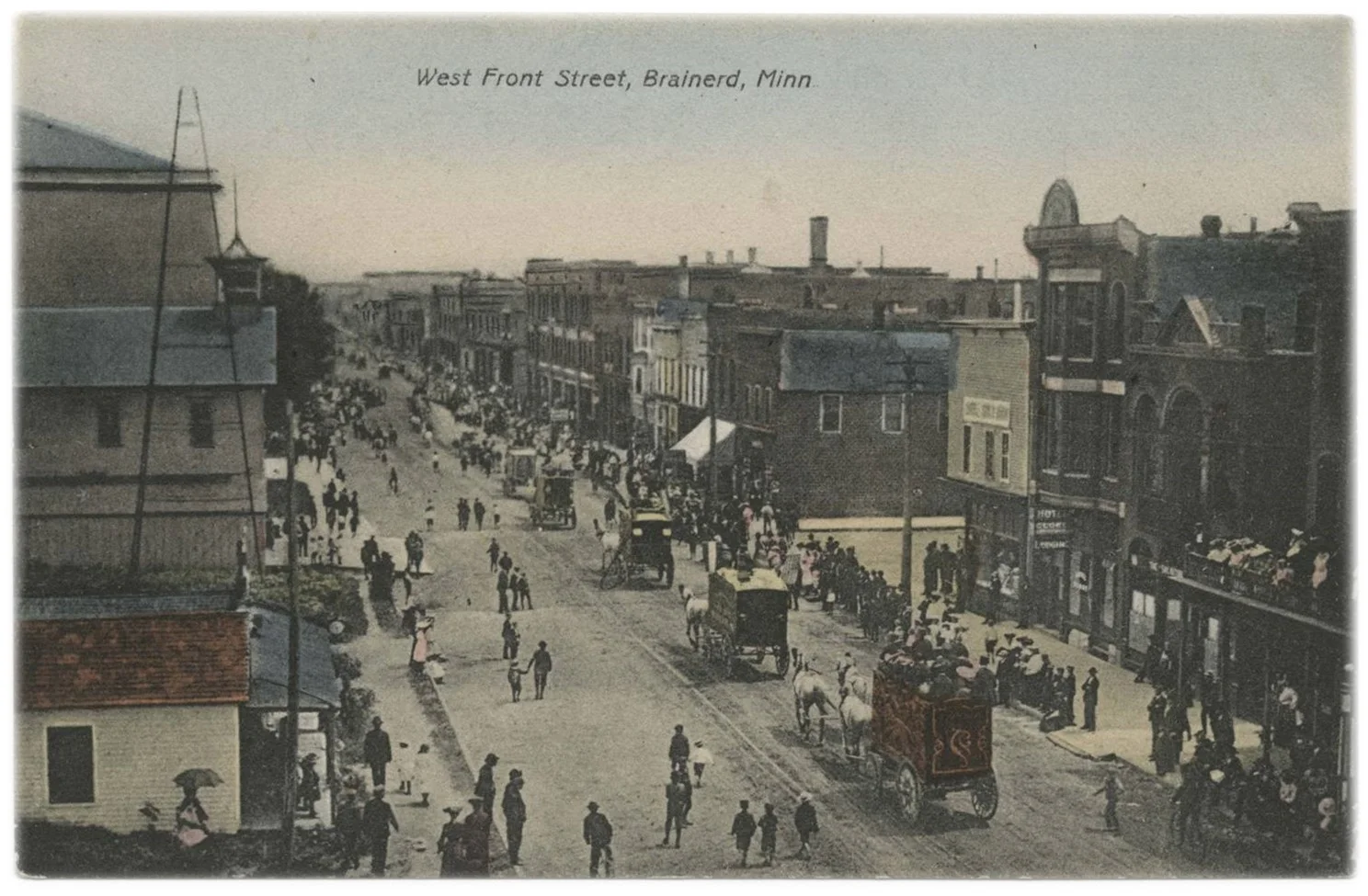

Here’s the second generation of buildings on this same street. Version 2.0:

Front Street. Brainerd, MN, 1894.

The two- and three-story wood structures on this street represent a significant increase in private wealth and value. That increase comes with a significant, but far lower, increase in public commitment in the form of a wooden sidewalk and gravel street. The modest increase in private wealth justifies and supports the modest increase in collective commitment.

Here’s the third generation of this street’s evolution. Version 3.0:

Laurel Street. Brainerd, MN.

This generation of brick and granite buildings had fully modern infrastructure systems. There were concrete sidewalks on the edges of an asphalt street. A storm drain is visible in the middle of the street, a way to shed rainwater into a pipe that would also transport sewage to the river. There is a fire hydrant on the corner indicating a water system. The increase in intensity of the street supported an increase in intensity of communal infrastructure.

Version 1.0 did not have enough private wealth to support any public investment. Version 2.0 had more private wealth, but could still only support modest amounts of public investment. Version 3.0 had a significant amount of private wealth and, correspondingly, supported a significant amount of public investment.

There is no chicken-and-egg conundrum here. Before the Suburban Experiment, private investment preceded public investment. The wealth generated by private investment is necessary to justify, and ultimately sustain, the collective public investment. This relationship is essential for long-term community stability.

Historically, rising private wealth in cities leads to increased public commitment. The city itself serves as the ultimate rentier, extracting ongoing income from the wealth of the community, for the benefit of the community. The stable relationship between private and public investment looks like this:

This approach will seem antiquated to many, especially those used to the Suburban Experiment way of building cities. Nothing we do today looks like this. Instead of private wealth leading, in today’s cities, it is the collective public investment that leads. Governments frequently invest millions of dollars, or make long long-term maintenance commitments worth millions, before any taxable private investment has been made.

In other words, the public sector takes on a significant amount of risk.

In the best-case scenario for a local government, a developer will agree to pay for the public infrastructure—all the roads, streets, curbs, sidewalks, pipes, pumps, valves, and meters—and do so completely at their own expense. The developer takes the first life cycle risk, the chance that the development does not cash flow adequately enough to cover the up-front expense.

What the city then assumes is the ongoing maintenance liability. The risk is that the development will not grow to have, or retain over time, an adequate tax base to fund ongoing maintenance costs. This is the best deal our cities ever experience today. Most cities do far worse.

For example, in addition to the long-term maintenance costs, some cities voluntarily incur financing risk during the development process. They serve as the bank for the developer by borrowing the money to build new infrastructure, using the good faith and credit of their taxpayers as security. The developer, in exchange, agrees to pay back the loan, with some interest, when the developed property sells (although sometimes that promise is transferred to the property owner at the time of purchase).

Some cities will forego working with a private developer altogether and simply acquire and develop a property themselves. The concept of a shovel-ready site, owned by the city and ready for transfer, with all the public utilities pre-installed, has become commonplace. These deals are often sweetened with tax subsidies, waiving of fees, and expedited permitting.

While these approaches are commonplace today, it’s important to recognize how the phasing has shifted. Instead of private investment leading, the public sector now takes the risks by being out in front of the development process. Here is what that relationship looks like:

None of this is to suggest that, throughout human history prior to modern times, the public sector never took risks to spur development. They did, it was just the rare occasion and not the rule. Today, the public sector backstops almost all private land development, either by direct investments upfront or by assuming long-term maintenance obligations before the tax base has matured.

While this might seem like a subtle shift, the impacts are enormous. Once in place, public infrastructure investments become sunk costs. Cities have the capacity to borrow large sums of money, or shortchange other parts of their budget, to make debt payments. This blunts the intensely motivating incentive of financial failure and replaces it with the more abstract notion of political failure.

If a private developer constructs a new building and that building sits empty from a lack of tenants, the crisis is financial. Even if the building is occupied, but at a lower cash flow than anticipated, there is tension that shows up on the private sector balance sheet. Do that too many times and the developer ceases to be a developer.

If the local government constructs a new building (or a new road, new pipe, new drainage way, etc.) and it sits empty from a lack of tenants, the crisis is political. It’s an embarrassment. Yes, there is an underlying financial problem, but the nature of local government accounting obscures it, making it an indiscernible drag on the overall budget.

Solving this political crisis is simple: stop the embarrassment. Get the building filled with something. Anything. Get someone connected to the pipe. Get anything built along that road.

When the local government leads the development process, the humans involved will understandably be highly sensitive to the immediate negative feedback (embarrassment) that comes with the appearance of failure. They will be less sensitive to the financial insolvencies that are obscured and left largely unexplored by accepted accounting practices.

Do that too many times and the city will find itself—inexplicably, by its own standards—financially constrained, unable to make good on the many promises and obligations it has made, despite the growth and development it helped promulgate. This is the inevitable outcome of America’s Suburban Experiment.

It’s impossible to say what happens next, but the large gap between what our cities have promised to do and what they can actually deliver makes it likely, or even unavoidable, that many neighborhoods with paved streets, running water, working drains, and other public services will have to adjust to not having those things.

That’s the consequence of being overly committed to an insolvent development pattern. It’s time to get working on a Strong Towns approach, instead.

We have to stop looking at the stagnation and decline of our blocks and neighborhoods as a normal part of the development process.