How Fannie Mae Puts a Chokehold on Local Home Financing Solutions

There are two different conversations taking place about housing. One happens in the world of housing advocacy. In this conversation, housing prices are seen as too high, and so the conversation tends to focus on how to bring housing prices down. The other conversation takes place in the world of finance. In that space, high housing prices are a feature, not a flaw. The financial conversation focuses on finding more ways for people to access debt.

It is my observation that the housing conversation tends to demonstrate a rather unsophisticated understanding of the financial conversation. That is the case with the simplistic supply/demand assertion that we can build our way to falling home prices. It also shows up in the widespread assertion that developer greed is the primary source of rising prices. While I share a lot of the same underlying motivations, I have personally struggled to engage with the housing conversation because I find it internally incoherent.

That is not the case with the financial conversation. The financial world, a world of predator and prey, is very coherent when it comes to housing. And very sophisticated. Those in the financial world see themselves as the predators. Those seeking housing are the prey. The sophistication comes with how the predators construct and market their financial products to the prey, as well as to the various mediators, go-betweens, and overseers that foster these transactions.

For example, in the 1990s, the Clinton administration created a collaboration called the National Partners in Homeownership (NPH). It was an unprecedented collaboration of regulators and the regulated: federal departments like the Treasury and the FDIC and private sector organizations like the Mortgage Bankers Association and America’s Community Bankers. The goal of this initiative was to increase home ownership levels by making homes more affordable for more people.

To that end, they merely expanded the playbook first developed in the Great Depression and then redeployed during the first decades of the postwar Suburban Experiment. For example, NPH called for a reduction of down payments. Fannie Mae—at that time a privately-owned Government Sponsored Entity (a private business with government backing)—responded by reducing down payment requirements from 10% to 3%. In 2001, Fannie Mae entirely eliminated the need for a down payment on mortgages they purchased.

Obviously, lower down payments means less skin in the game for home purchasers, which means greater risk for lenders. The NPH called on the insurance market to address this risk by expanding the use of private mortgage insurance. Insurers such as American International Group (AIG) stepped up their issuance of these policies. (Spoiler: That didn’t end well for AIG or for the federal government.)

Another NPH innovation was the credit score. Up to this point, qualifying for a mortgage meant meeting with a banker for a very intimate and very intense underwriting process. With one human sitting in judgment of another human’s ability to assume a mortgage, all of the human failings—all of the -isms—crept into the process. An algorithm that calculated a credit score for each borrower was considered a much cleaner way to evaluate worthiness.

Conveniently, it was also a great way to issue more debt, especially to poorer people. Frank Raines, who was the chairman of Fannie Mae at the time, claimed that “lower income families have credit histories that are just as strong as wealthier families.” LOL. Raines put Fannie Mae’s (government-backed) money where his mouth was by increasing the amount of ultra-low down payment mortgages Fannie Mae purchased by 40 times in the 1990s.

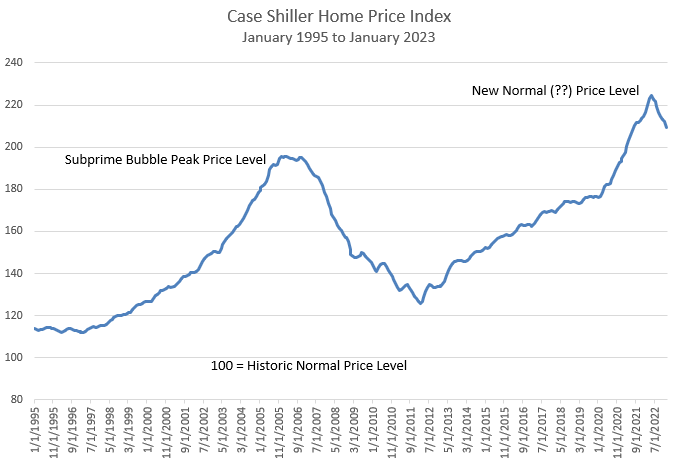

With others joining in, the housing market soared, both in terms of the number of people who purchased homes (goal achieved) and the price of that housing (goal achieved). Here’s the Case Shiller home price index from 1995 through the start of 2008.

This orgy of debt and price appreciation didn’t end well for Fannie Mae. Or, perhaps it did. In September 2008, as one part of the larger subprime housing crisis, Fannie Mae was rescued/nationalized and placed under the control of the federal government. It has remained nationalized for more than 15 years now.

Last month, Fannie Mae announced the launch of a “Single-Family Social Bond Framework,” a set of criteria used to create a financial product they call a Social MBS. This is marketing to investors, letting them know that they can feel good about putting their money where their heart is. By investing in Fannie Mae’s Social MBS, investors are helping allocate more credit in support of affordable housing so that “more people have better access to credit.” Fannie Mae’s marketing suggests they are working on the challenges of the housing market, especially those challenges “that disproportionately burden lower- and moderate-income borrowers and renters.”

This is the kind of thing you’d see in a Super Bowl commercial, complete with a compelling profile of the family being assisted by Fannie Mae’s lending program. It is also the kind of marketing that soothes the concerns of many housing advocates, just enough to keep the focus elsewhere (like those greedy developers). Show me the numbers, Fannie Mae, and they responded with a Social Index Score that does just that. It’s great marketing.

Once again, in the name of having more people take on more debt to pay more money for more homes, Fannie Mae is lowering down payments and extending loans to people with little to no equity and marginal credit scores.

If this seems insane, it is, but understand that 2008 wasn’t the first time we tried this. It was just the biggest bubble this set of strategies had created. That is, the biggest bubble up to that point. Here’s the Case Shiller Index as of the end of 2022.

Want a real commercial—not the kind you’ll see during the Super Bowl, but the kind experienced in cities all across North America?

In Detroit, there is a house occupied by a family paying rent to a landlord. That landlord acquired the house through the tax foreclosure process. The landlord may have paid $15,000 for it at a tax auction; the family now pays $700 a month to live there. It is likely that the same family paying rent now was living there when the prior landlord—whose business plan included not paying their taxes—defaulted and lost the home in tax foreclosure, a process that takes five years in Michigan (in this instance, not paying your taxes for five years is simply a wise business strategy).

Take the $15,000 purchase price and divide by $700 per month in rent. That’s a tad more than 21 months, less than two years. The family living in that house could have owned it outright in less than two years had they been the ones to purchase it. So, why didn’t they?

The answer is simple: there is no financial product to facilitate that transaction. Fannie Mae, despite the marketing of a Social Good MBS, is not going to purchase that mortgage. The margins are just too small. They won’t purchase it and so nobody originates it; that’s how vertically oriented local banks are. There are hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of these transactions that could happen—all of them profitable and socially beneficial—but Fannie Mae has no real financial incentive to bundle them up, securitize them, and create a secondary market for their purchase. So, they don’t happen.

And not only are the margins too small, a proliferation of this product (an entry-level housing product at a much lower price point) undermines the entire foundation of housing finance and, by extension, the entire foundation of our banking system (because securitized mortgages make up such a large percentage of bank reserves). It undermines everything, because such a broadly affordable product will slow, perhaps even reverse, housing price appreciation. That is also bad for Fannie Mae.

Fannie Mae, and all the other purveyors of centralized capital, are not interested in pursuing strategies that make housing broadly affordable. In fact, they will oppose any policy that actually makes prices go down. They are happy to provide more loans to more people, to increase the amount of debt we consume as a society, because that makes housing prices go up, which is what centralized capital requires.

And they are happy to listen to the housing advocacy conversation, if only to discern just how to market their financial products in the most socially affirming way possible.

This whole thing won’t change until that Detroit family can easily finance the $15,000 foreclosed home they are paying rent on, a transaction that requires less capital than most auto loans. This is not a liquidity problem. It won’t be solved by lowering interest rates or printing more money. It can’t be fixed by originating more mortgages to securitize, by lowering down payments, or by extending terms to riskier borrowers.

This is a structural problem. It is the result of a social, political, financial system that is centralized and top down. The next Strong Towns book, Escaping the Housing Trap, comes out on April 23. With it comes a transformative conversation about the power of bottom-up action to change the way housing is done in North America.

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.