Are Officials Hiding the True Price of This Bridge Project?

This article was originally published, in slightly different form, on Strong Towns member Joe Cortright’s blog City Observatory. It is shared here with permission. In-line image was provided by the writer.

The Interstate Bridge connects Vancouver, Washington, with Portland, Oregon, and it needs to be replaced. But officials from the Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR) project aren't telling people how much it'll cost to actually finish the job.

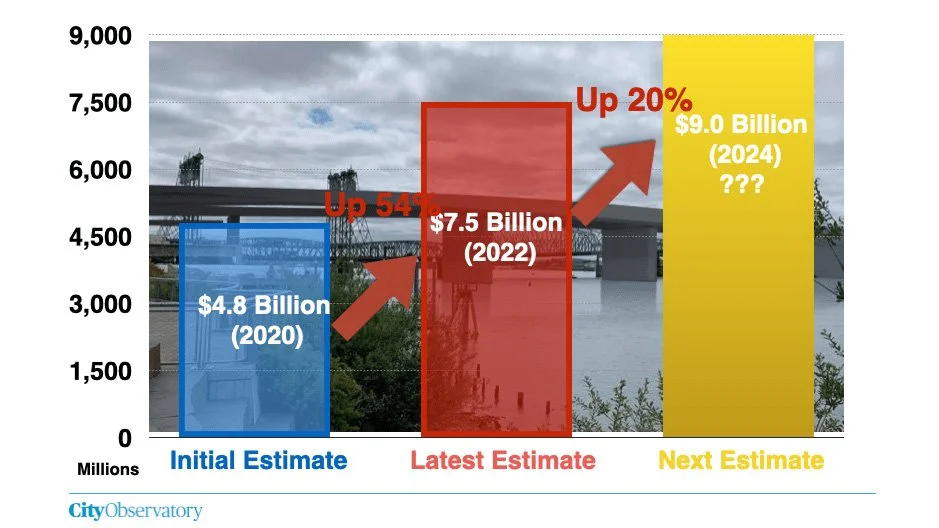

The project is already two years behind the schedule announced when it was restarted in 2020, and it's falling further behind. The cost of the project has ballooned from a maximum of $4.8 billion in 2020 to as much as $7.5 billion in 2022. Then, in January of this year, IBR officials publicly acknowledged that this 13-month-old estimate was wrong and promised a new estimate “later this summer.”

It’s now summer, and, at a June 13 Community Advisory Committee meeting, project director Greg Johnson conceded that the IBR’s budget was going up again, but said the new estimate won’t be done until “about this time next year” (June 2025).

A Chronology of Cost Estimates

No one should place much credence on IBR cost estimates: they always go up.

November 2020: The initial cost estimate is $3.3 billion to $4.8 billion.

May 2022: City Observatory predicts that costs will rise to between $5 billion to $7 billion. As Willamette Week reported, City Observatory's prediction — made in May 2022, seven months before the IBR estimates were released — was spot on, and even slightly conservative.

December 2022: The new cost estimate is $5 to $7.5 billion. IBR officials confidently assured alarmed legislators that they would prevent future cost increases thanks to the Cost Estimate Validation Process (CEVP) the Washington Department of Transportation used to manage risks. City Observatory filed a public records request for that CEVP, and in January 2023, IBR officials claimed that “no records exist” of any CEVP work.

January 2024: IBR Director Greg Johnson says that “costs are going up. We are going to be reissuing an overall program estimate probably later this summer.”

June 2024: IBR testifies THAT it will do another cost estimate “about this time next year.” Greg Johnson, in comments to the IBR’s community advisory group, elaborated:

It was our plan to go into another ... cost validation estimating process that looks at risk and evaluates and puts a cost to risk. And so the last time we did this, which was two years ago, we came up with the range between five and seven and a half billion. And that seven and a half billion was the worst-case scenario at that time. But once again, as we have seen, the outpacing of inflation rates beyond what anybody was expecting in the construction industry, those numbers are going higher. We are seeing it across the nation on large construction projects, so we expect that number to be higher. We were going to start another CEVP process on the heels of getting the draft supplemental document done. But now, as that has been pushed, we are pushing that CEVP to understand what we are building. So ... it will probably be around this time next year that we will have that final process completed with a more rigorous and up-to-date number for overall construction costs.

June 2025: The next cost estimate is likely going to be $9 billion or more.

Lying and Concealing Cost Increases

The IBR is the single largest highway project in Oregon history, and will severely strain the managerial and financial capabilities of ODOT. Even as Governor Kotek says ODOT faces “catastrophic funding challenges,” the need for additional funding for the IBR project is also consistently omitted from ODOT’s lengthy financial presentation. ODOT has been participating in hearings around the state on its financial condition, and its presentations never make any mention of the state’s liability for these cost increases for the IBR. By postponing the next cost estimate until the summer of 2025, ODOT is concealing this information from the Oregon Legislature as it debates a major transportation measure.

This process is a classic example of what Bengt Flyvbjerg diplomatically calls “strategic misrepresentation” — what we would more colloquially call lying. In this case, it takes the form of lowballing the cost estimate to get the project started and get an initial commitment of funds, and then jacking up the price tag when it's “too late” to consider anything different.

The agency has essentially no process for managing or preventing cost increases. The price of the Interstate 205 Abernethy Bridge has tripled to $750 million; the price of the Interstate 5 Rose Quarter project has quadrupled to $1.9 billion. And the financial tools that ODOT says it uses to control costs, grandly called the “Cost Estimate Validation Process,” do nothing.

As City Observatory has pointed out before, the CEVP doesn’t manage or prevent risks so much as it documents how devastating they are when they occur. In the case of the Columbia River Crossing, the CEVP process failed completely to identify the cost and schedule risk of the Coast Guard’s decision not to agree to a 95-foot navigation clearance, which added more than a year and tens of millions of dollars to the project’s cost. In the case of the IBR, just this year, the CEVP process grossly underestimated the likelihood and schedule risk of IBR’s flawed and outdated traffic models. They were thought to add no more than six months to the project's timeline but are now understood to delay the project by as much as 18 months.

ODOT is touting a newly announced $1.5 billion federal grant for the project. But the project’s price tag is rising faster than ODOT is finding money to pay for it, and Oregon and Washington will be left holding the bag for any cost increases or toll-revenue shortfalls.

Joe Cortright is President and principal economist of Impresa, a consulting firm specializing in regional economic analysis, innovation and industry clusters. Over the past two decades he has specialized in urban economies developing the City Vitals framework with CEOs for Cities, and developing the city dividends concept.

Joe’s work casts a light on the role of knowledge-based industries in shaping regional economies. Prior to starting Impresa, Joe served for 12 years as the Executive Officer of the Oregon Legislature’s Trade and Economic Development Committee. When he’s not crunching data on cities, you’ll usually find him playing petanque, the French cousin of bocce.