Today in the United States, about 11% of children walk or bike to school. Compare that to 1969, when 40.7% of students walked or biked to school. The North American pattern of development produces an expectation that every child will be driven to school either on a bus or in an automobile. The thought of a child walking to school is foreign because the built environment has been deliberately transformed in ways that make it unsafe and nearly impossible for children to do so.

For the past three years, my son attended a school in the heart of our neighborhood's little downtown. This school is a piece of local history, having been built in 1929 as one of the first public schools in the community. We live 0.7 miles from the school, which translates to about a 15-minute walk. We have an infinite number of routes through the neighborhood to choose from, making this an enjoyable experience.

My son is now entering middle school. His new school is also part of local history, as the second school which opened its doors in 1959. It's also located only 0.7 miles from our home, but it's in the opposite direction, in the geographic center of the residential neighborhood. I had a lot of excitement anticipating another three years of walking my son to school, but I have discovered the walk to the middle school is nearly impossible.

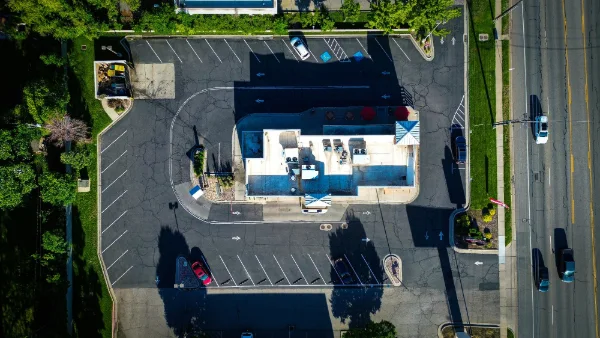

The school shares a dead-end street with 20 single-family homes. The only measurable traffic on the street is from the middle school in the form of parents and buses transporting 640 children. Despite this, the area lacks the bare minimum infrastructure needed to accommodate people walking. Instead, its infrastructure prioritizes high-speed car traffic.

The street is over 28 feet wide with a double yellow centerline. The street is wider at the intersections, where paving has been added to accommodate higher-speed turns and where the paving crews were generous during the last repaving project. There is no sidewalk. These physical conditions, along with the school being the only destination on this street, encourage drivers to drive at fatal speeds. The result is 100% reliance on automobiles or buses for children to access the school.

These two schools are in sharp contrast with each other, despite them being the same size and located within relatively similar residential neighborhoods. One school is highly walkable, providing multiple safe options for students to access the school. The surrounding lots have seen incremental investment and growth. The middle school has not experienced incremental investment over the past 65 years and is frozen in time. This is just one of the many negative outcomes of the choices people have made in the pursuit of the Suburban Experiment.

A critical civic institution within my neighborhood, whose primary users cannot drive, leaves those users at the mercy of the school bus or the privilege of an adult with a car. This frustrates me both as an urban designer and a parent, and my frustration deepens knowing that our community has had 65 years to address this. I would like to walk my children safely to school. This should not be an unreasonable expectation.

I carried this frustration home to my drafting desk and asked myself, "What is the next smallest thing I can do to address this struggle? What is a low-cost and quickly deployable action that could yield a safe walking path for students and parents like myself?"

The first step was to consider what I knew about the street. While attempting to walk to the middle school several times, I'd made several observations that could help me identify simple opportunities to address the struggle.

My first observation was the width of the asphalt. The street is really wide, which contributes to excessive speed. Each travel lane exceeds 10 feet in width, which is wider than the majority of the roads in our local neighborhoods. When I took a few measurements, I found that the street is over 28 feet wide.

My next observation was that one side of the street is adjacent to the school and football field and has several "no parking" signs. The decision has already been made that one side of the street shall not have parked cars which is enforced by a handful of signs.

A more subtle observation was the double yellow centerline that is painted the entire length of the street. A double yellow is typical on high-volume roads or highways, not residential streets. This type of striping informs the driver that this is a high-speed road and encourages them to drive at speeds incompatible with a neighborhood street. Additionally, the striping is a little haphazardly installed, drifting from the center of the street and making one lane larger than the other.

Taking into consideration all of these observations, I was able to outline a few simple steps to create a safer street that would let children walk to school:

1. Remove the Double Yellow Line

First, I would remove the haphazardly painted double yellow line. The removal of this striping would visually transform the street from a high-speed highway back to a local residential street. This subtle change is important to communicating the behavior expected of drivers on the street.

2. Narrow the Travel Lanes

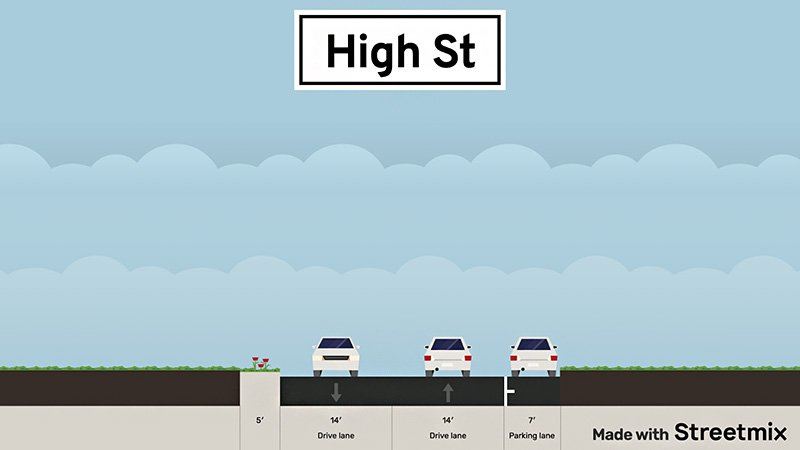

Next, I would resize the travel lanes to reflect the character of the residential neighborhood. Together, the two lanes on this street are over 28 feet wide. If the striping was in the center of the street, that would result in 14-foot-wide travel lanes — two feet wider than highway lanes.

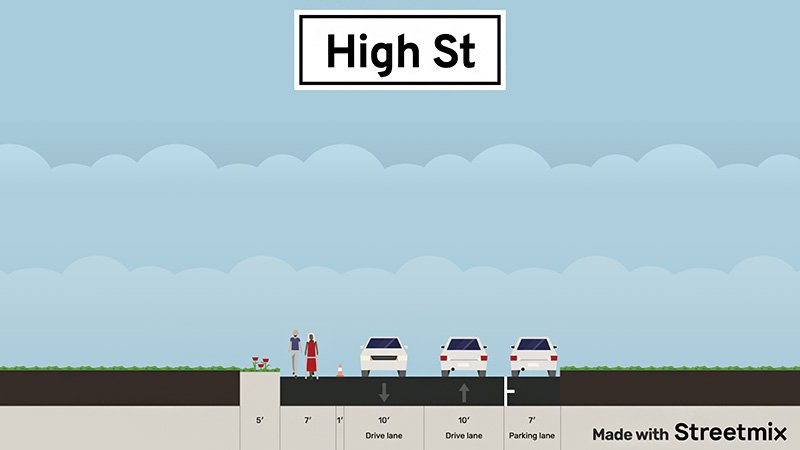

I'd narrow each travel lane to 10 feet wide for a total of 20 feet of roadway. The extra asphalt could be yielded to people walking. This would result in 20 feet of asphalt dedicated to the movement of cars and buses and a minimum of 8 feet of asphalt dedicated to people walking.

The area’s paving contractor has actually started the process of narrowing the street already. During the last repaving, the contractor stopped 6 feet short from the curb in front of the school. Whether this was a budget-driven or commonsense decision, it illustrates that narrower travel lanes are possible.

3. Create an Area for People To Walk

Finally, I would turn the remaining 8 feet of asphalt into a space for people to walk. I recommend that this walking area be located adjacent to the school. This eliminates the conflicts with driveways and is in a location where parking is already prohibited. This new walking area could be delineated with paint, bollards or curbing. These features could be deployed in an afternoon with temporary materials for pennies of the cost of constructing a concrete sidewalk. Over time, as budgets allow, these temporary improvements can be made permanent.

These are the next smallest steps that parents and neighbors could undertake in coordination with the city to address this struggle. With only a minimum amount of effort, my community could have a safe walking route to the school. This does not require a lot of money, and it could be tackled in a morning or afternoon with the resources readily available today. The community would not have to wait for a grant, conduct an extensive study or hire an engineering consultant. It can simply emulate the conditions found on the surrounding streets and transform some excessive pavement into a productive walking area.

This formula for improvement is observable and repeatable. How will you apply it in your place?

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)