In a few weeks, I’ll be hanging up decorations, pumping balloons full of air and baking a cake. I’ll pick up my son and hold him tight while friends and family gather around to sing "Happy Birthday," joyfully celebrating his first year of life.

As any parent knows, the first year is a mixed bag: It’s exciting to watch a little baby grow up, but it’s also a bit sad to watch the baby fade away and the toddler take its place. Already a walker at 10 months, Levi is bolting as fast as he can into the next phase of childhood and it’s marked by endless curiosity. He has no problem walking laps around the apartment exploring anything and everything: kitchen drawers, the laundry basket, the inside of the fridge. Sometimes, he’ll sit on the floor and just examine his hands more closely, moving them around in funny ways. Outside, he wants his hands in the dirt, on the leaves, in the water. Animals, he wants to watch and imitate.

With the weather getting cooler and backpacks going on sale, I’m reminded that his curiosity won’t die down anytime soon; it’s only going to grow. Before I know it, we’ll be trading sensory play and his beloved copy of "Brown Bear, Brown Bear" for math lessons as he matures into more structured learning.

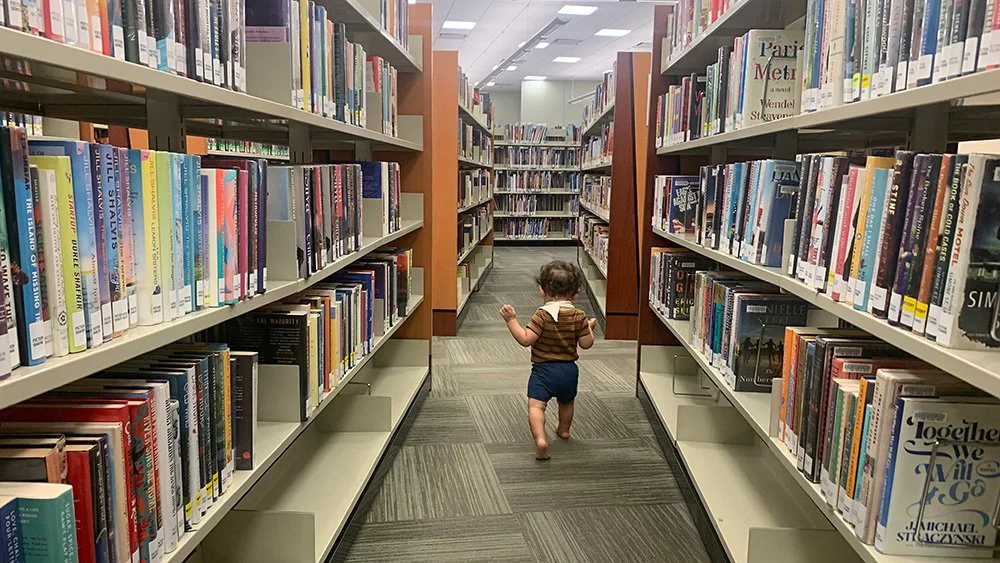

Personally, I love back-to-school season and I can’t wait to walk alongside Levi as he becomes a student. But the curiosity of his toddlerhood reminds me that learning has already started. Learning is happening right now at every moment. Learning happens while moving around his immediate context: the home, the yard and the community at large.

Some of my favorite memories of Levi so far are from times he’s explored the world outside our home. At the National Gathering this past spring, he made immediate friends with Strong Towns staff members. Here in town, I let him walk around independently in my line of sight at the coffee shop, at the post office or around the cafeteria of the college where my husband works. I love watching people stop what they’re doing to watch him, to smile and wave, to talk to him, to help him stand up if he falls.

These moments have reminded me of “Children in the City,” one of my favorite chapters from the book "A Pattern Language." Children, the authors contend, learn by watching and imitating adults. It is by this observation that they learn about the world and what it means to be part of society. But this means children need to be around adults, in the real world, in the city: “If the child's education is limited to school and home, and all the vast undertakings of a modern city are mysterious and inaccessible, it is impossible for the child to find out what it really means to be an adult and impossible, certainly, for him to copy it by doing.”

Obviously, children need dedicated safe spaces to play and learn, but when we look at the design of our cities, what is available to them beyond these spaces? What options do they have for exploring, observing and participating in the city at large? Unfortunately, this is nearly impossible in most cities for reasons we know all too well: “There is constant danger from fast-moving cars and trucks, and dangerous machinery. There is a small but ominous danger of kidnap, or rape, or assault. And, for the smallest children, there is the simple danger of getting lost. A small child just doesn't know enough to find his way around a city.”

From the moment they’re born, children are asked to adapt to a car-oriented world. Their first foray into the outside world usually happens while strapped into a car seat, from which they cannot see the world nor the faces of their driving parents. As they grow up, their movement is constantly managed. The ability to move freely exists in a few pockets: the schoolyard, maybe their neighborhood street, maybe the church playground. The rest of the world is seen mainly as a place of danger. Everything comes with a warning: “Look before crossing,” “Hold my hand,” “Be careful.”

Ironically, this doesn’t get better when the children get older. Even when they pass their driving tests and obtain their long-coveted licenses, the cost of participation is still high both financially and psychologically, with constant reminders to “drive safe” and to not text and drive. We all bear a cost for the design patterns we’ve chosen, but for children, the cost cannot be understated.

I think again about those memories of watching Levi interact with strangers at our third places around town. Perhaps this is one way forward: carving out pockets wherever we can with children in mind. Maybe this could look like asking small businesses in town to host “watch and learn days” where older children can, well, watch and learn while the adults work. Perhaps it's asking coffee shops to put a few toys out for parents coming with their littles. Maybe it’s starting a bike bus or asking the city to occasionally close a series of neighborhood streets so children can explore the neighborhood.

Our cities and the world at large are not designed for children, but, through relationships and intentionality, we can carve out spaces for them where they can explore independently, where they can interact with and learn from neighbors, where they can observe the world, and, more importantly, where they can be part of it.