Editor's Note: The challenges our cities face are growing, but so is the strength of this movement. Every story we share, every idea we spread, and every tool we build exists because people like you are committed to showing up. Your membership isn’t passive—it’s the momentum that makes change possible.

Last week, the Federal Reserve met and lowered interest rates for the first time since March 2020, during the early panic weeks of the pandemic. In market terms, there is talk of this rate cut kicking off an easing cycle, an extended period where economic conditions loosen and money flows more freely.

I admit to being more than a bit bewildered by it all. Over the years, I've gone to some lengths here to describe the impact that loose monetary policy has on local project decisions, how we literally induce the worst developments, and how turning housing into a financial products price — like all financial products in the era of cheap money — diverge from all financial reality.

Bewilderment hasn't been the reaction in housing circles. With lower rates, the monthly payment applied to a 30-year mortgage goes further. This makes housing more attainable for more people, or so the story goes. It's a financially illiterate story. Holding the monthly payment steady and lowering interest rates merely allows all market competitors to pay more for the same house. Lowering interest rates doesn't make housing prices more attainable; it just makes the current housing stock more expensive.

Even Canada, a country generally more sane than the United States on housing finance (though the gap is closing quickly), announced that they are making housing more attainable by making it easier for more people to borrow more money. One Canadian economist noted that “there is a risk that this simply stimulates homebuying demand, puts more pressure on prices and ultimately makes affordability worse over the longer run.”

With housing serving primarily as a financial product, as it does today, the greater market sensitivity is over prices falling. Yes, policymakers and politicians will lament the lack of affordability, but everyone understands that the way to make housing prices go up is to make it easier for more people to borrow more money to pay more for housing.

So, that is what we do.

At the end of Chapter 5 of "Escaping the Housing Trap," I made a prediction about the future of housing finance. I wrote that “housing prices may adjust downward slightly over a short timeframe. They may even drop dramatically if markets temporarily spin out of control. Either way, there will always be a coordinated effort to reinflate the housing market. There must be; if the housing market fails, the financial system fails. That is the lesson from 2008. It is even more true today. This makes the next innovation in housing finance somewhat predictable: the 50-year mortgage.”

We're not quite there yet, but there are now serious conversations going on about making a 40-year mortgage into a mainstream financial product. One of the leading voices advocating for this product is the founder of Operation HOPE, John Hope Bryant. In a CNBC op-ed, Bryant wrote that “a 40-year mortgage allows more people to begin building equity sooner, offering a pathway to long-term financial stability and sustained human dignity.”

It’s not exactly clear what Bryant means by “building equity sooner.” After a decade of making (mostly interest) payments on a 40-year mortgage, a homeowner will have reduced their loan by only 8%. This isn’t a path to building equity; it is debt slavery to big banks.

It is worth noting, again, that the 30-year mortgage is one of the worst financial products imaginable. That is why it didn't occur naturally, why the federal government had to create the market for them. It is also why the federal government has had to prop up this market over and over through a series of housing bubbles, each one larger than the last.

When interest rates go up, banks lose money on their lower interest rate-bearing mortgages. They are forced to pay depositors more in interest but, with a fixed-rate 30-year product, they can't adjust their loan portfolio to compensate. This story has played out over and over again, forcing multiple bank interventions since the Great Depression.

When interest rates go down, banks would love to hold onto those 30-year mortgages that are now paying premium interest rates. The spread between that income and the lower rate they need to pay depositors is very lucrative. Yet, this is exactly the time when all those homeowners with higher-interest mortgages go and refinance at a lower rate. End of lucrative investment.

For banks, long-duration mortgages are a "heads you win, tails I lose" kind of proposition. This is why the federal government is so heavily involved in the financial side of the housing market — it wouldn't exist without federal support. Successive rounds of financialization have made housing prices more sensitive to capital flows than to local supply and demand dynamics.

The idea of a 40-year mortgage can only come from a place insensitive to what it means for an individual or a family to take on such debt servitude. As Josh Rosner wrote in a famous paper in 2001, a home without equity is just a rental with debt. With a 40-year mortgage, the buyer is merely renting from the bank, pledging decades of their future earnings to the holders of mortgage-backed securities and their various derivatives. Yet, unlike a rental, a holder of a 40-year mortgage can't move without tremendous financial costs.

That is, unless home prices go up. The only thing that would make anyone buy a home with a 40-year mortgage is if housing was not shelter but an investment. If the price of the house goes up faster than the interest rate, then taking out a 40-year loan is a path to wealth creation, not by paying down the mortgage, but by living in the home while it goes up in price.

In a decade, the homeowners paying the 40-year mortgage may have reduced their debt burden by only 8%, but — if the home grows at 8% a year in value — their $400,000 home investment will have more than doubled in price to $860,000. That’s a different version of the American Dream, one fully captured by Wall Street, one where housing prices must continue to climb for Americans to prosper.

That's how we end up needing to establish a new set of beliefs about how housing markets function.

After all, if we all just believe, we can make that new paradigm a reality. The more people are willing to believe, the more they will be willing to borrow more money to pay more for housing. The more they pay for housing, the more prices will climb. And on and on.

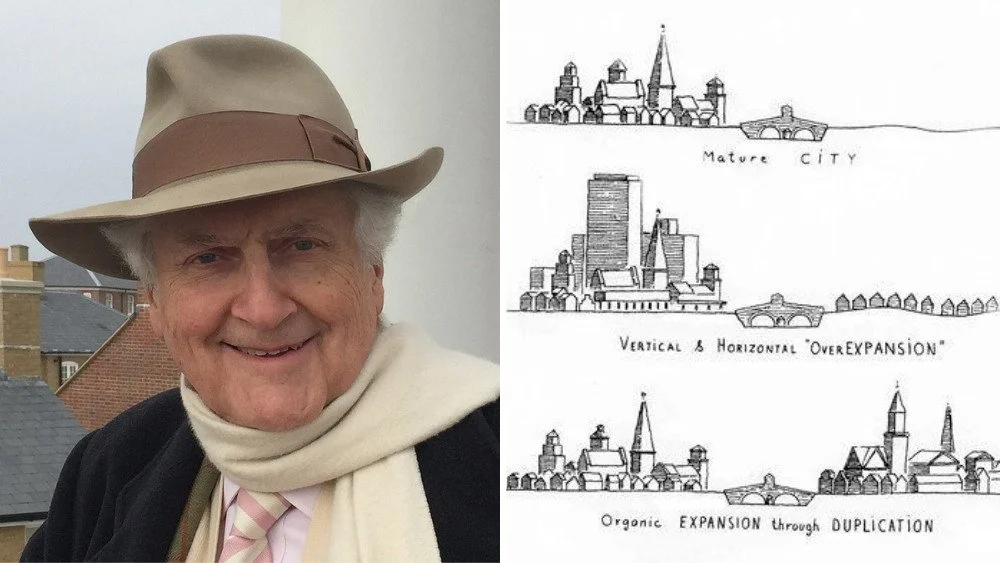

There is only one thing that arrests this cycle: filling the market with locally financed, locally built, low-cost, entry-level housing. We need a housing market that is locally responsive to supply and demand dynamics, one where there are plenty of entry-level, affordable products.

The only competition for the dynamics of a top-down, centralized housing market is a bottom-up, locally-responsive housing market. In such an economy, anyone could opt into big financial products — and that might make sense for certain investors — but everyone can opt into shelter.

And that will stabilize prices for everyone.

.webp)