3 Ways To Make This Chicago Megaproject a Success for Everyone

A proposed redevelopment in Chicago that would replace parking lots with a walkable, mixed-use entertainment district.

Beyond the storied architecture of downtown Chicago, there are a few famous Chicago landmarks that attract visitors from around the world. The United Center, longtime home of the NBA’s Chicago Bulls and the NHL’s Chicago Blackhawks, is one of those places. Recently, the destination has invited a different kind of public attention due to a planned redevelopment effort.

This massive new proposal, dubbed the 1901 Project, is a $7 billion private investment to redevelop the parking lots surrounding the sports arena into a mixed-use entertainment district with hotels, businesses and residences. According to the project website, the project will “transform the West Side with a jolt of new development, bridging neighborhoods and enhancing opportunities for residents, businesses and all of Chicago.”

The city of Chicago is facing a budget shortfall of nearly $1 billion, and this privately funded megaproject is certainly an enticing opportunity, considering that it both offers to invest in an economically depressed neighborhood and is projected to provide over $100 million in annual tax revenue.

Google Maps satellite view of the United Center and the ocean of parking lots surrounding it.

I’m glad that the 1901 Project leadership recognizes the value in trading convenient venue parking for housing, retail and other amenities that generate far more benefits than car storage. However, a sudden deluge of investment from a megadevelopment centered in a previously deprived and sensitive neighborhood is already posing major challenges on all sides.

Left: An aerial photograph of the United Center as it stands now. Right: A rendering of the 1901 Project. A night and day difference.

The Public Outreach Meeting

The 1901 Project held its first public outreach meeting on August 27, 2024, in a conference space within the United Center itself. The room was absolutely packed, with many people — including myself — forced to stand for the entire presentation. The development team showed beautiful renderings to outline the broad strokes of their vision.

There was a lot to like. Outside of the aesthetics, the team appeared to genuinely prioritize transit and a people-friendly experience. They included protected bike lanes on major streets, highlighted the proximity to current bus routes, and even proposed partnering with the city to add a train station that would bring service within 1,000 feet of the arena.

Renderings of the 1901 Project, including a music hall, an ice skating rink, a pedestrian walkway connecting two buildings, and a park built on top of a parking structure.

After the introduction, the presenters explained that the 1901 Project is slated to proceed in multiple phases, represented by different colors in the diagram below.

A diagram of the multiple phases of the 1901 Project. Each phase is represented with a distinct color. Photo taken during the 1901 Project public outreach meeting.

This diagram is clearly intended as more of a sketch than a detailed blueprint. I translated this onto a mosaic of Google Maps screenshots to visualize the proposal in more real-world terms, matching it to streets and existing properties as best I could. The first phase of the project is represented by the three blue rectangles in the image below.

Google Street View satellite image mosaic of the United Center with color overlays for each phase of the 1901 Project, as shared at the public meeting in August 2024. The first phase (blue rectangles) is labeled with letters corresponding to an A) park, B) music hall, and C) mixed-use building. Projects A and C also incorporate significant parking.

Slated to break ground as early as summer 2025, the first phase consists of (A) a park built on top of a parking structure ringed with ground floor retail, (B) a 6,000-seat music hall, and (C) a mixed-use building including hotel rooms, retail and parking. The development team estimated that the first phase would take between two and three years to complete. Combined with the number of phase colors, this suggests that the entire project would take at least a decade to complete.

The response from the community during the outreach meeting was not positive. Several audience members decried the 1901 Project, worrying that they would be pushed out of the area by gentrification. Several seniors were concerned about how their apartments across the street would be affected. A few people were interested in the business opportunities the project could provide, but the tone was overall one of fear, anger and hurt.

There is no clean solution to the tangle of problems that has plagued the nearby residents and their homes for the better part of a century. I certainly don’t have a perfect answer for how the 1901 Project leadership can have their development and a good relationship with the community too. Nonetheless, there are a few ways they can approach the project that can give everyone a chance to benefit — or at least minimize the harm that sudden, large change can do to a community.

Break It Up

Google Maps satellite view image of the United Center with blue rectangular overlays for the first announced phase of the 1901 Project.

Currently, the 1901 Project has only shared details of the first phase of development. Judging from the renderings, the project managers should consider breaking these big parcels into much smaller pieces. There are several reasons for this. Large, complex building projects that take years to complete are more sensitive to economic factors like rising costs of labor, interest rates or building materials. These rising costs can leave projects stalled indefinitely or ultimately abandoned at great cost.

Working on a larger number of smaller projects may be more complex, but this approach is more resilient and often faster, with simpler projects wrapping up far more quickly. Additionally, by slicing up the property into smaller parcels, local business partners can be involved at lower price points, spreading the risk and reward to more people.

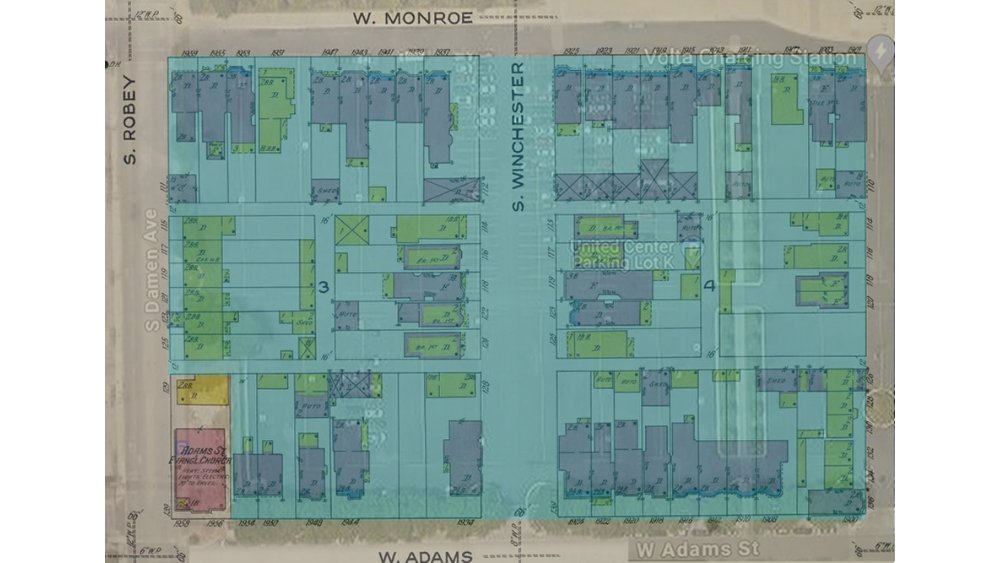

There are other factors to consider as well. Here is a specific example from the first phase of development. There is a proposed 6,000-seat music hall, which would seat more than the Sydney Opera House. By comparing the lot size of the music hall — an estimated 400 feet by 500 feet — (denoted with a blue rectangle in the image below) to fire insurance maps of the same area that were drafted in 1917, we can see that the footprint of this music hall was once more than four dozen smaller properties.

Google Maps satellite view image of the United Center with a blue rectangle representing the proposed music hall, overlaid with Sanford fire insurance maps showing how the land was divided in 1917.

We’ve lost this fine-grained urbanism in this area. We also lost South Winchester Street, which used to cut right through the middle of the proposed music hall parcel. I recognize that the 1901 Project developers are unlikely to slice up their properties into the original single-lot sizes shown in these maps, but the impact of such a move is worth considering. Respecting the old street grid and rebuilding South Winchester Street would split this large parcel in two and still offer plenty of room for a smaller music hall on one half.

The next step would be reinstating the old alleyways that used to interlace these city blocks. The 1901 Project could have the music hall on one side of South Winchester Street and four medium-sized developments on the other.

One possible way the 1901 Project could subdivide the parcel for the 6,000-seat music hall is to reinstate the alleyways and South Winchester Street from the old street grid.

Respect the Interface

The 1901 Project team should respect the interface between their project and the existing neighborhood fabric. They should understand the context of their block in terms of both design and the needs of the local community.

There are lots of ways to do this. At the bare minimum, the team should take care not to have large empty expanses of building facades face neighboring properties. Blank walls are corrosive to the pedestrian experience. They are boring to walk past and contribute to an area feeling less safe. Even worse than blank walls would be allowing major eyesores like parking garage entrances, dumpsters or large building utilities to face the street.

Instead, the buildings on the edge of the 1901 Project should mesh as much as possible with the community and offer something to that community. For example, the music hall parcel I discussed above is directly north of Malcolm X College. The 1901 Project team could consider splitting the parcel as I suggested above and developing mixed-use residential buildings with coffee shops, bars or restaurants on the ground floors. These could be enjoyed by students alongside the music hall.

Left: Google Maps satellite view image of the United Center with a bright pink rectangle highlighting a property parcel that is currently empty. Right: Google Maps street view image of the vacant parcel, outlined in a dashed bright pink rectangle.

As another, more residential example, consider the small vacant lot in the image above. This street consists of single-family and multifamily homes, with a larger mixed-use building on the corner that has a daycare on the ground floor. Given the proximity to two elementary schools and the daycare, a great choice for this vacant lot would be a mid-rise building with family-sized units, ideally featuring architecture and building materials that blend in with the block.

Being respectful of the neighborhood interface and need, whether on single lots like in this example or on stretches of city streets, will help build goodwill with the community and integrate the 1901 Project more smoothly into its surroundings. In short, it shouldn’t be easy to tell where the 1901 Project begins and ends.

Get Ahead of Toxic Speculation

This last suggestion falls on the city of Chicago. When small areas are subject to intense increases in zoning, it often fuels stagnation and speculation on surrounding streets. There is little to stop an investor from purchasing aging, cheap housing or vacant lots and holding onto the property as development ensues around it, raising the price of the land with no effort on the part of the investor.

City of Chicago zoning map of the blocks surrounding the United Center (PD-522).

Ideally, Chicago’s leaders would consider the surrounding context of the 1901 Project while they consider the development itself. Allowing the next increment of development by right would let existing property owners, say, convert their home to a duplex for additional rental income, without the costly and time-consuming process of applying for a zoning change. Proactively allowing incremental development in the immediate area can alleviate the stressful dynamic this megaproject presents to neighboring properties, allowing existing local owners the opportunity to profit from the new investment without being strangled by red tape at city hall.

Another option to consider is a land value tax. Conventional property taxes tax not only the land but also the buildings and other improvements on a site, thus making development and local investment less appealing. Land value tax only taxes the land itself, encouraging neighborhood investment and renewal.

Chicago officials should also continue to invest in programs supporting small developers, especially residents of this neighborhood. It isn’t possible to undo the injustices and lack of investment that this community has suffered. However, by being respectful of the current residents’ needs and building out the development incrementally, the 1901 Project could be a rare megadevelopment that is not only completed but is also enjoyed by all.

Chloe Groome is a founding board member of Strong Towns Chicago, a Local Conversation based in the windy city. She has a PhD in Materials Science and Engineering and a lot of opinions about architecture and urban planning. Her favorite hobbies are writing, knitting and attending contentious zoning meetings. Long time listener, first time contributor, she has been following Strong Towns and the urbanism movement for nearly a decade and is thrilled to be here. You can listen to her discuss her journey on The Bottom-Up Revolution here. Join the Strong Towns Chicago mailing list, follow on Instagram, and be sure to join their Slack to start building a better Chicago.