Small Town America vs Big Box Stores

"That sense of identity and place that homegrown businesses create—that’s what we want to preserve here," Sean Donaghy told the local news back in February.

In 2013, Sean and his wife, Amy, purchased the building that now houses the Washington General Store. More than just a place to pick up essentials, the store has become a gathering space where locals can grab a hot meal or stock up on everything from chainsaw oil to craft beer. Their customers include farmers, out-of-towners, and a motley crew of regulars. “Someone will come in and brighten my day, or I’ll brighten theirs just by a conversation,” Sean said. “You think it’s just small talk, but it’s more than that—it builds relationships.”

The Washington General Store in Maine.

But now, much of what the Donaghy’s love about their town is under threat. A 4,000-plus-square-foot Dollar General is slated to open in this town of fewer than 2,000 people. "It absolutely detracts from what Washington is and hopes to be," Sean said. Kathleen Gross, another local, put it bluntly: "We don't want a corporate, faceless box store coming in with no stake in our community."

The concern isn’t just about the immediate hit to small business revenues. Local farmer Jeffrey Knox worries about the broader impact on Washington’s economic ecosystem: "We want our money to stay local, and we like to invest in each other and our community.”

The Big Box Swindle

The residents of Washington are right to fear that a big-box store like Dollar General would take a lot and give very little in return. A 2023 report by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR) found that in both small towns and larger urban settings, dollar stores push out local grocers and other retailers. In doing so, they limit access to fresh food, siphon wealth from local economies, foster crime and violence, and undermine the long-term resilience of the communities they enter. Put another way, the convenient access to low-cost goods comes at a steep price.

“We want our money to stay local, and we like to invest in each other and our community.”

Yet over the last five years, Dollar General has opened over 3,500 new locations, including more than 100 in New York, nearly 200 in Ohio, and 300 in Texas. This expansion has brought the total number of Dollar General stores to over 18,000, solidifying its position as the largest retailer in the U.S. by store count. Looking ahead, the company plans to further grow its network, aiming for more than 51,000 outlets in the coming years.

Some argue that the rapid expansion is simply the chain fulfilling fast-growing demand. When Dollar General first arrives and shoppers choose it over the homegrown alternative, this is no different than the market expressing its preferences. As the saying goes: “evolve or die.” That’s what one hardware store in New Orleans, Louisiana did to remain competitive with the growing number of big box retailers in the vicinity.

“We feed off of what they don’t do, they can’t do,” the owner of Mike’s Hardware & Supply explained. Part of that looks like emphasizing his longtime staff’s expertise. Another part of it is simply providing goods you can’t find anywhere else. “We don’t sell barbecue pits or lawn mowers, but we have a lot of hard-to-find specialty items, especially in plumbing, that they don’t have,” the owner added. “We’ve evolved to our niche.”

While Mike's Hardware has successfully carved out a space amidst larger-than-life competitors, the real problem with the competition between Dollar General and mom-and-pop stores is that the playing field isn't level. Few will be as lucky as Mike’s.

In fact, a key driver behind the rise of big-box retailers is the extensive government support they receive, including subsidies and billions of dollars to fund their expansion, says Stacey Mitchell, co-director of the ILSR. In an episode of the Strong Towns podcast, she explains how companies like Walmart or Target convince local officials that they’re bringing jobs and financial benefits to the area often in exchange for tax breaks and subsidies to cover the cost of land or construction. Unfortunately, many local governments are too quick to take the bait.

Walmart, for example, received subsidies for one out of every three stores it built, pocketing over a billion dollars from local governments. A Dollar General in Haven, Kansas demanded the taxpayers of the town of less than 2,000 inhabitants to foot the store’s $72,000 utility bill on the promise of jobs and tax revenue. That’s how much it cost to run Haven’s public library and pool for the year. The town caved and subsidized approximately half the bill.

ILSR also discovered that large corporations benefit from tax loopholes, enabling them to avoid paying income taxes in about half the states they operate in. Meanwhile, small businesses don’t have that luxury—they pay taxes on 100% of their earnings.

This uneven playing field places local businesses at a disadvantage, as they are required to bear a higher tax burden than their corporate competitors. A similar dynamic plays out on the federal level, where corporations may operate in part through shell companies based in tax havens.

How locals can fight back

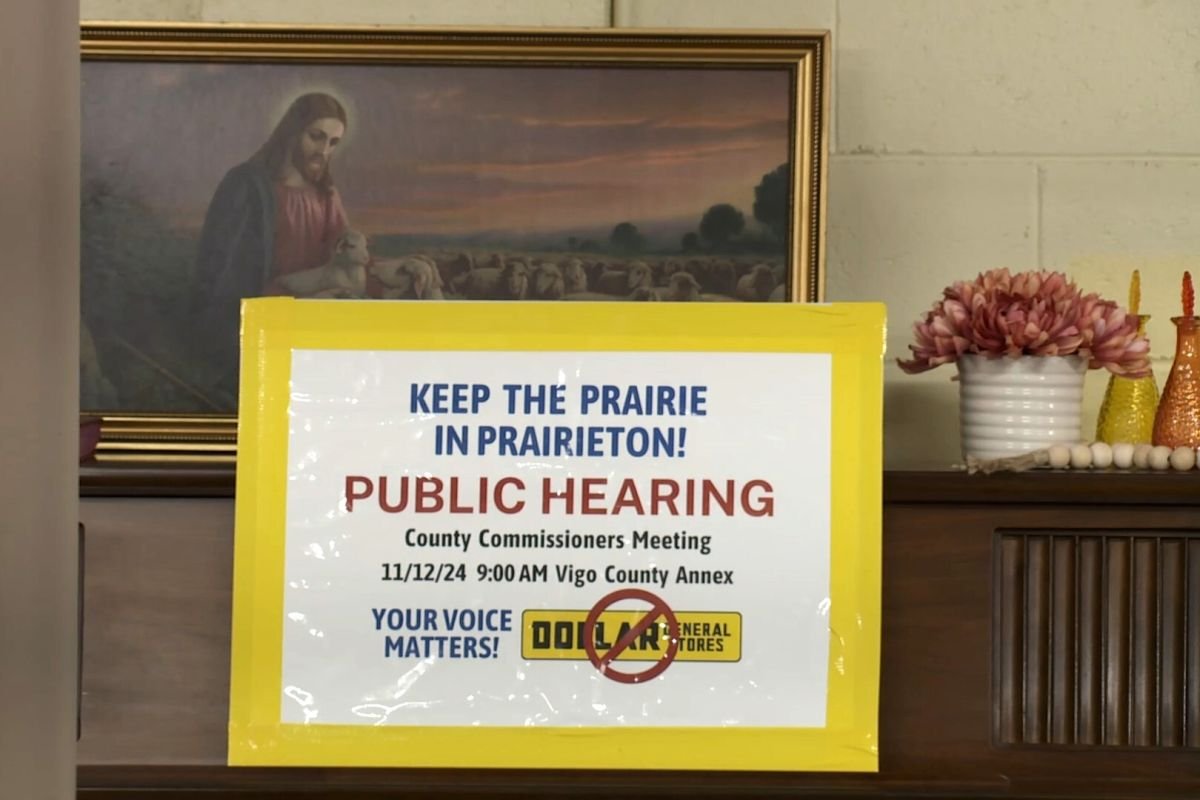

In Prairieton, Indiana, residents successfully blocked the construction of yet another Dollar General—it would’ve been the third within an eight-mile radius. They persuaded the county commissioner not to rezone the farmland where the store was planned, rallying under the slogan “Keep the Prairie in Prairieton.” At first glance, their opposition might seem like a textbook case of NIMBYism, a term often used to dismiss those who resist change in their communities. But the reality was more nuanced.

The residents weren’t opposed to rezoning the farmland outright. In fact, at one point, the idea of building homes on the site was discussed. “We’d much prefer to have homes and families,” Cindy Morgan, a leader of Keep the Prairie in Prairieton group told the news. “We need houses… It's just the whole idea, you know, we're not against change, we're not against business, if you want to open a nice little coffee shop and bookstore, but Dollar General just isn't quite a good fit.”

Their objection wasn’t to development itself—it was to what they saw as an unproductive use of the land. As one sign at a town hall put it: “Don’t Pave Prairie-dise to Put Up a Parking Lot.”

Some of the signs seen in the basement of the Prairieton United Methodist Church. (Clayton Baumgarth/WTIU News)

Since 2019, at least 75 communities have blocked proposed dollar stores. Cities like Birmingham, Alabama; Fort Worth, Texas; and Plainview, Nebraska have even enacted laws restricting where these stores can open. Stonecrest, Georgia has arguably gone the furthest, according to the ILSR, by imposing a total ban on new dollar stores.

Now, in Washington, Maine, Donaghy, Gross, and others opposing Dollar General are figuring out their next steps. Earlier this year, the town approved a six-month moratorium on non-residential developments over 4,000 square feet, buying time to explore what policy levers they can pull to push back against what Gross calls a “faceless corporation.” But are bans the best way to ward off the dollar store invasion?

In the short term, yes. A ban prevents the store from taking root in a neighborhood. But it doesn’t address the deeper question of economic vitality, says Edward Erfurt, Strong Towns’ Chief Technical Advisor. A truly thriving community wouldn’t need to court the jobs, commerce, and other “perks” that a big-box store promises—nor would it feel threatened by one.

If locals want their money to stay local long term, Erfurt suggests they start by rethinking what policies on the local level inadvertently privilege corporate giants. Many land-use laws, for example, seem almost tailor-made to benefit big-box stores, while making it harder for homegrown businesses to take root and thrive.

Take parking minimums. Stores like Walmart or Dollar General have the financial resources to acquire large parcels of land on the outskirts of town, where large parking lots are easy to build. In fact, these stores often want excessive parking, he adds, because it both makes access easier for car-dependent customers and crowds out smaller competitors. Meanwhile, a small café or hardware store in a historic downtown core might be required to provide the same number of spaces per square foot, even though it operates in a walkable area with street parking nearby. Meeting these mandates often forces small businesses to buy additional land they can’t afford, demolish usable buildings, or abandon downtown locations altogether in favor of auto-oriented strip malls.

They're bad policy even in communities where "everybody drives." Rather than allowing businesses to tailor parking to their needs, mandates impose a rigid, one-size-fits-all requirement that forces businesses to subsidize land they might not need or want. In cities that have reformed or eliminated these rules, businesses still provide parking—but in ways that reflect the area's context, their budget, and actual demand.

→ Read Death By Parking, the story of how Dallas’ parking mandates stood in the way of a coffee shop.

Cities are shaped by a patchwork of land-use regulations that may seem reasonable or well-intentioned, but in actuality serve as another barrier to keeping local money local. Besides parking mandates, minimum lot sizes, setback requirements, and completely isolating commercial from residential uses make it difficult for small businesses to operate in traditional, walkable downtowns, where space is limited and adaptability is key. Ironically, most businesses operating in historic downtowns wouldn’t be able to exist under today’s regime of rules.

Just say no

Outside of code reform, local policymakers need to recognize that the short-term “wins” of landing a big-box store rarely translate into long-term prosperity.

Whatever temporary boost in sales tax revenue big-box stores generate quickly fades, leaving behind low-wage jobs, struggling local businesses, and a tax base that can barely cover basic infrastructure maintenance. Furthermore, Urban3, a consulting firm specializing in spatial financial analysis, has consistently shown that land occupied by dollar stores and big-box retailers generates shockingly little tax revenue compared to traditional downtown development. Their research has demonstrated that even hundred-year-old derelict buildings in so-called “failing” downtowns often outperform these subsidized retailers, producing more value per acre than a brand-new big-box store.

Comparing the value per acre (VPA) between Main Streets in North Carolina and one of the largest, most recognizable big box retailers, Walmart.

Put bluntly: These massive, low-density retail footprints consume enormous amounts of land and resources while contributing very little in return. Their parking lots sit empty most of the time, and when they inevitably close or relocate, they leave behind a blighted, tax-draining shell that’s expensive to repurpose.

Then there’s the simple fact that, unlike locally owned businesses, which reinvest earnings into the community, national chains extract wealth, siphoning profits to corporate headquarters.

Building local prosperity won’t happen overnight, but accepting the Faustian bargain of a Dollar General may compromise those efforts. Communities nationwide are recognizing this and pushing back. It's time for local leaders to listen.

For local governments serious about long-term financial resilience, chasing big-box stores isn’t the solution. When Dollar General opened in Haven, Kansas, it wiped out the town’s only other stores within just three years. And when it inevitably closes, as many of these chains eventually do, residents will be left with no local options, vulnerable to the same cycle repeating itself.

Rather than subsidizing national retailers with short-term promises, cities should invest in policies that empower local entrepreneurs and adopt land use strategies that favor homegrown businesses over corporate chains.

If you want to understand where your town’s finances are heading, check out the Strong Towns Finance Decoder.

Asia (pronounced “ah-sha”) Mieleszko serves as a Staff Writer for Strong Towns. A dilettante urbanist since adolescence, she's excited to convert a lifetime of ad-hoc volunteerism into a career. Her unconventional background includes directing a Ukrainian folk choir, pioneering synaesthetic performances, photographing festivals, designing websites, teaching, and ghostwriting. She can be found wherever Wi-Fi is reliable, typically along Amtrak's Northeast Corridor.