Stanwood Mulls Strong Towns-Style Main Street Makeover

This article originally appeared on The Urbanist. It is republished here with permission.

Main street Stanwood is currently dominated by cars. (Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

Stanwood, Washington, a fast-growing town 25 miles north of Everett, is considering overhauling its main street to embrace walkability and good old-fashioned main street urbanism. The effort is being championed by Councilmember Steve Shepro, who is an adherent to the Strong Towns approach to building financially resilient places.

Strong Towns has long cautioned against the creep of stroads, a portmanteau of “street” and “road” referring to overly wide, high-speed roads through commercial districts prone to collisions and ultimately economic decline. Shepro sees Stanwood as beset by a stroad, and he’s seeking an identity for the town that is more centered around walkability and small business vitality.

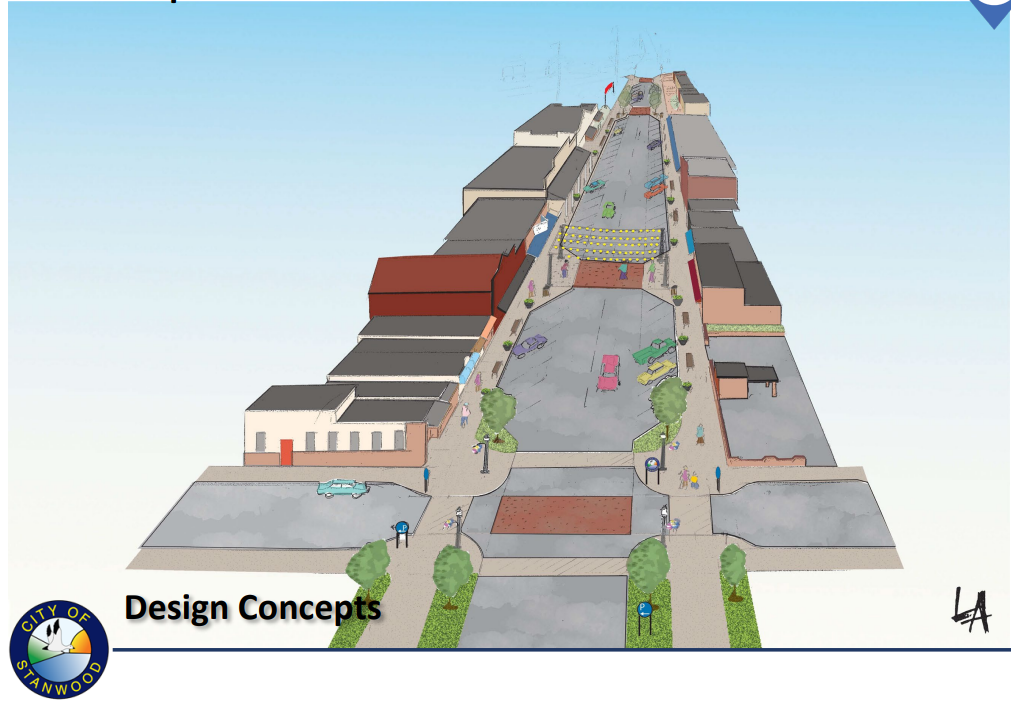

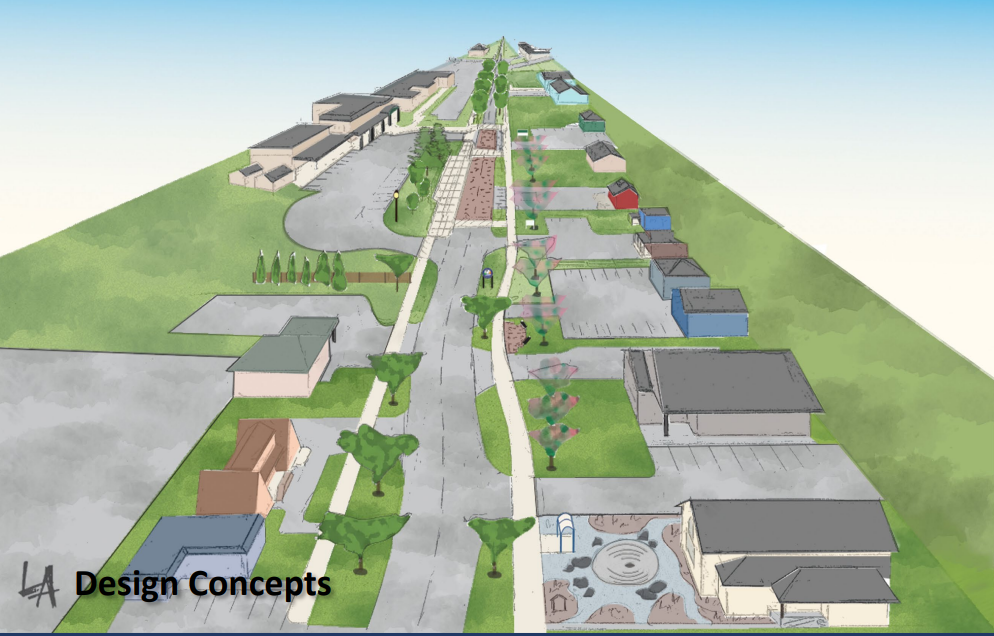

The downtown revitalization proposal, which is being called the Twin City Mile, is seeking to improve walkability and street life along 270th Street NW and 271st Street NW, a mile-long stretch of the main streets in Stanwood that connect the Amtrak train station to City Hall Park. The proposal suggests widening sidewalks, adding engaging storefronts, planning for street festivals, creating usable urban park spaces, public art, and promoting the concept of buying local.

(Click to enlarge. Source: City of Stanwood.)

Stanwood is 50 miles north of Seattle on the mouth of the Stillaguamish River and in a floodplain that also includes the mighty Skagit River. The town of 7,700 residents is also the gateway to Camano Island—a popular getaway and retirement spot home to about twice as many people as the town itself. Stanwood also functions as the primary business district for the island, given the dearth of commercial activity on it.

Highway 532, which runs through Stanwood, is the only land route to Camano Island. As a result, the two-lane highway has a tendency to back up, causing impatient drivers to use Stanwood’s streets targeted for the Twin City Mile project as a cut-through route to avoid traffic snarls. Relatedly, speeding on through the neighborhood is common, Shepro said, with motorists frequently going 35 or 40 miles per hour even through the 20 mph school zone.

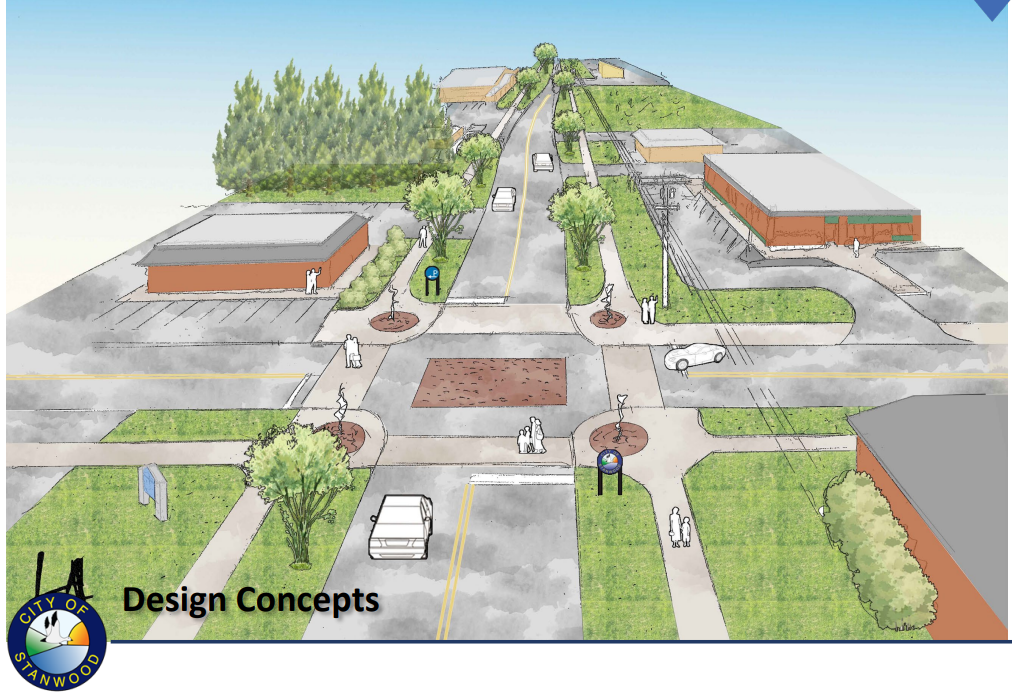

(Click to enlarge. Source: City of Stanwood.)

“Our main street in between West Stanwood and East Stanwood is a perfect example of a stroad,” Shepro said. He noted the highway department is also under pressure to widen Highway 532 to four lanes, but he opposes that change, adding he “doesn’t feel the need to drive fast everywhere.”

The two main commercial nodes in the town are centered on the west and east ends of main street, but the middle part is a bit of a dead zone. Shepro said this is the section that feels most dangerous and unpleasant as a pedestrian. The two ends of town also have distinct feels, which is a vestige of Stanwood formerly being two separate towns, East Stanwood and West Stanwood, before unifying in 1960. The project website notes the goals of both better connecting the two ends of town and also establishing more cohesive design elements throughout the entire streetscape.

Apparently, the tiny town of Stanwood, WA (pop. 7,200) elected some land use and transportation people to their Council and now they're working hard to fix their downtown stroad. pic.twitter.com/s1GtzZbpO2

— Queen Anne Greenways (@QAGreenways) May 10, 2022

Stanwood’s main street is the commercial center of the area, but part of what draws many people to Stanwood is its bucolic charm. Located far from the rest of Snohomish county’s suburban expanse, it’s surrounded by fertile farmland, forests, and the Salish Sea.

“There are a lot of people in Stanwood who are attached to the rural lifestyle,” Shepro said. “They have chickens in their yard. They have no desire to see a [big] box store anywhere near us. They want to retain the rural character of the city, and that’s part of our Comprehensive Plan right now. It dwells a lot on retaining that rural atmosphere.”

At the same time, Shepro said more and more residents are looking for more urban amenities as Stanwood grows. Shepro has also been a big proponent of expanding and upgrading Stanwood’s park system, and noted the city could use a greater variety of restaurants, stores, and coffee shops. The city is intentional about keeping its small-town character as it grows, though. In 2005, Stanwood rejected a proposal to add a Walmart superstore in town due to pushback that it would devastate main street businesses. The “buy local” element included in the proposal is similarly intended to bolster small businesses.

Stanwood isn’t a big tourist draw, like La Conner on the other side of the Skagit delta or Camano Island, but there is some interest in seeking to promote tourism. Shepro said it would take investment and time, but the revitalization project would further the process.

Stanwood is also being affected by the work-from-home trend and spillover from Seattle and Bellevue employment centers. Shepro noted folks used to shopping for homes to the south of Stanwood look at $650,000 homes as a “screaming bargain,” but that price is beyond the means of many Stanwood locals, who see lower wages than folks commuting (or telecommuting) to Seattle, Bellevue, or Redmond. Stanwood home prices have jumped more than 25% in a year, similar to many suburbs in the Seattle metropolitan area. Zillow has the average Stanwood home value pegged at almost $717,000.

“Housing affordability is a huge problem here right now,” Shepro said. “But we are seeing tremendous interest from developers and homebuilders. I don’t know if that’s going to mean relief or not. A lot of homebuilders are just building bigger houses that cost more, and I’m not sure where the new income for these houses is coming from, other than people commuting to Seattle where the wages are much higher.”

The recent waves of development haven’t been focused downtown due to its location on a floodplain. But a townhome complex in the works in downtown might overcome the challenge of added insurance costs of building in a floodplain, Shepro said. He also noted the city is seeking to upgrade its flood rating: the City has moved some civic buildings out of vulnerable areas and embarked on a 10-year project to redesign its stormwater system. In the meantime, the hill just east of downtown is outside the flood zone and has been a hive of development activity.

Despite the recent spike in home values, Stanwood is not a wealthy town, Shepro said, and its tax base is limited. The hope with the Twin City Mile is to fund the project largely through grants, and defining the project will help determine which grants would be a good fit.

This inspiration board shows main street at 102nd Avenue. (Source: City of Stanwood.)

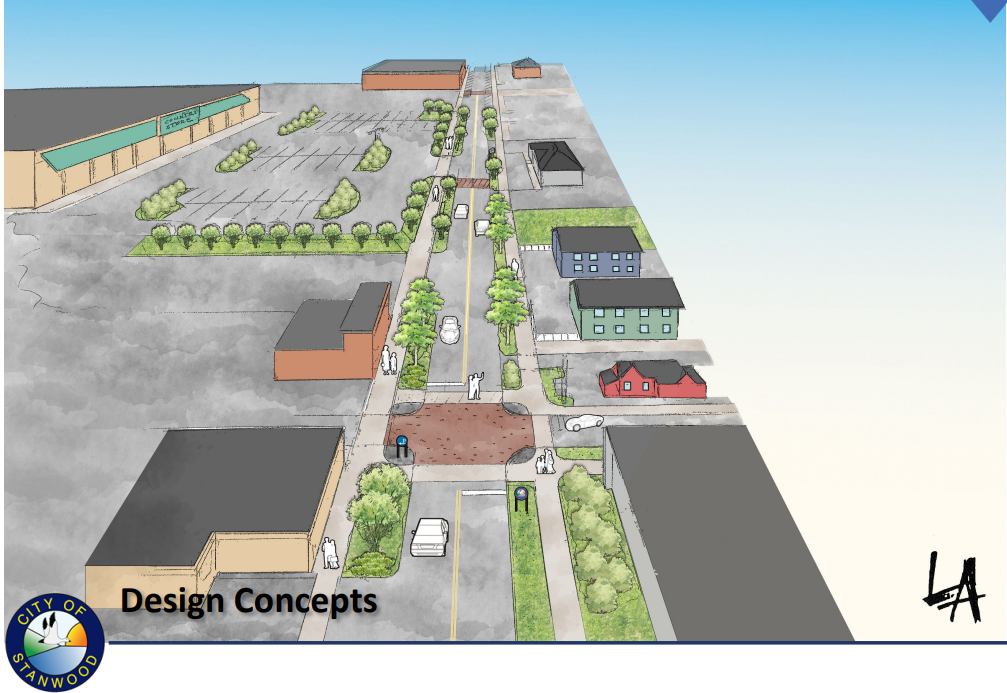

The 270th West Section would retain angle parking in this vision. (Source: City of Stanwood.)

Beyond funding, the other major challenge the Twin City Mile revitalization will face is the same challenge nearly every urban street redesign faces: parking concerns.

“If you make it parallel parking you could widen the sidewalk, but if you make it parallel parking you could park less cars. There’s one shop owner I talked to, and I suspect there are others, who would freak out about that idea,” Shepro said. “They see no advantage in losing any parking, whatsoever.”

Still, Shepro is confident the downtown revitalization plan will win out.

“I suspect there are more people who are interested in making the downtown over with wider sidewalks and maybe sidewalk dining and things we don’t have any of right now,” Shepro said. “There’s going to be those people who if it takes 30 seconds longer to get to QFC because we’ve made the road slower, they’re going to be unhappy. It’s the way it’s going to be, but I don’t think they are going to prevail.”

Stanwood City Council is expected to take action in August.

Doug Trumm is the executive director of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrianizing streets, blanketing the city in bus lanes, and unleashing a mass timber-building spree to end the affordable housing shortage and avert our coming climate catastrophe. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington. He lives in East Fremont and loves to explore the city on his bike.

The dollar store invasion has hit rural Maine. Banning the retailer is one way to stave it off, but how can locals guarantee long-term financial resilience?