Why Do Americans View Zero Road Deaths as an Impossible Goal?

The news has made the rounds since the new year began that Oslo, Norway has hit a remarkable milestone in its push for safe streets. Not a single pedestrian or cyclist was killed on Oslo's streets in 2019. Only one person was killed at all, and it was a driver whose vehicle struck a fence.

This achievement follows decades of steady progress. The idea of Vision Zero, which began in Scandinavia, has fittingly seen a real-life demonstration in Scandinavia.

And yet the usual American response to the whole idea that it's possible to achieve zero road deaths in a year is dismissive laughter. Hands in the air if you’ve heard one of these refrains recently:

"Of course you don’t actually mean zero, right?”

“I mean, there will always be accidents!”

“There are bad drivers out there! You can’t fix stupid.”

Oslo proves Vision Zero is not a utopian rallying call but something that can be done. It's a question of priorities.

In fact, from a physics standpoint, the whole problem comes down to something very simple. A car that strikes a person while traveling slower than about 15 to 20 miles per hour is very unlikely to kill them. So Vision Zero as a design problem is just this: eliminate all instances where a driver could hit a pedestrian at a speed greater than 15 to 20 mph, even if one or both parties make a mistake.

This means in places where people will be out and about (i.e. streets), cars and trucks must either be kept out entirely, or must not travel faster than 20 miles per hour. Period. The design must be such that even a driver who isn't inclined to be law-abiding won't dare go that fast. Here's what that looks like, in a photo from Oslo:

Oslo also owes much of its success to aggressive efforts in the last few years to outright remove cars from many core areas, as Curbed details here. In more details documented by Streetsblog, the city has applied an everything-at-once strategy of simultaneously building out bike infrastructure, reducing speed limits, establishing vehicle-free “heart zones” around schools, using congestion pricing as a step toward a car-free urban center, and instituting strict penalties when traffic laws are violated.

On the other hand, in places where cars must be allowed to go faster than 20 miles per hour (i.e. roads), pedestrians should be strictly prohibited. There should be few of these in urban areas—the point of highways is to move people between productive places, not within them. Here's one in Oslo:

It’s a simple rule. No cars moving fast enough to kill a person in places where people are going to be. No people in the (rare) places where we allow cars to move fast enough to kill a person. That's it. It's not, at its core, about enforcement, or clever design, or better signage, or even better, more attentive, more conscientious humans. It's about speed. Speed is what kills.

When you think about what would actually have to change in American cities in order to achieve that change in our travel speeds, that's where it gets messy, though. Vision Zero is a simple engineering problem, but a wickedly complex social and institutional problem.

The Tough Talk: How Unsafe Speed is Embedded in the Way We Live

North America is unlike much of Western Europe in that a much greater share of people live in places that are not only designed for travel at speeds several times greater than 20 miles per hour, but under their current arrangement would simply cease to function if we could no longer travel at those speeds.

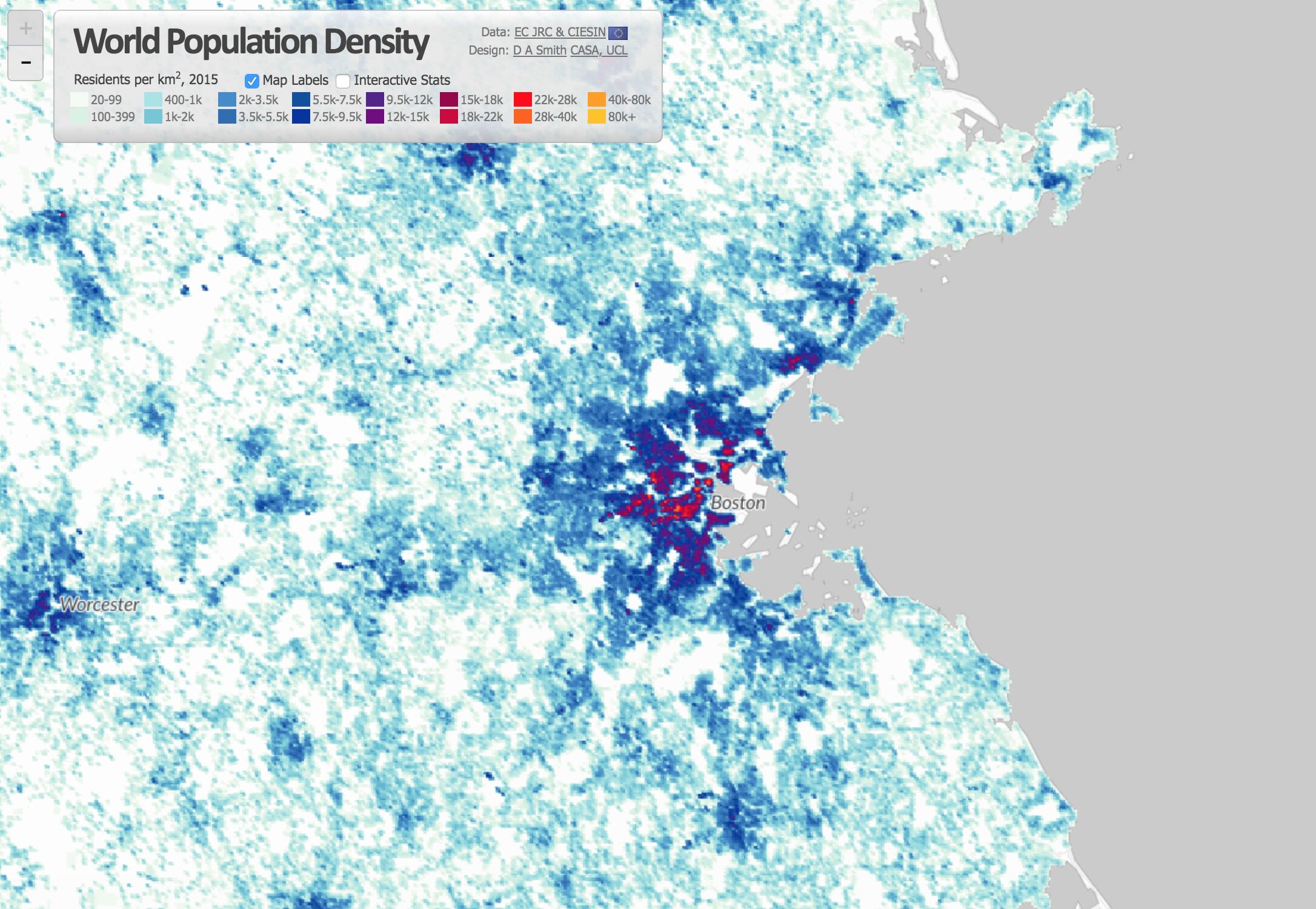

Here, at the same scale, are population density maps of metropolitan Oslo and Boston:

“The great tragedy of the American postwar development pattern is that we’ve built a world where a productive life is only possible if we do our daily travel at truly crazy, historically unprecedented speeds.”

Central Boston is actually more densely inhabited than central Oslo. The most visible difference between the two cities, though, is the relative absence in Oslo of the light-blue suburban blob that surrounds Boston.

It's in that suburban blob that Vision Zero becomes politically intolerable, because the land-use pattern is entirely designed around 30 to 70 mph travel. The houses are far apart, with big lots. The street networks are circuitous. The shopping, office, and residential areas are all isolated from each other. If you suddenly imposed 20 mile-per-hour travel in this environment, you would actually be dramatically impeding people's ability to get where they want to go in an amount of time they're willing to spend. If you could wave a wand and do so overnight—say, by putting a speed limiter on everyone's cars—you'd incite riots in no time.

(Vision Zero also receives political pushback in America's dense urban cores, because we've configured them to accommodate suburban car commuters. To a large extent, in fact, we've configured our urban transportation systems to prioritize access for car commuters over the safety and comfort of those who actually live in urban neighborhoods.)

It's not speed itself—the feeling of moving fast—that we're wedded to, I don't think. Not so much that we value it over other people's lives. It's our time that is so precious to us we’re often willing to sacrifice safety for it. It's our ability to go about the day and get everything we need to done in a reasonable duration. The great tragedy of the American postwar development pattern is that we've built a world where a productive life is only possible if we do our daily travel at truly crazy, historically unprecedented speeds. These are speeds that make doing everything by car (with the attendant risk of injury or death, to yourself or others) the unavoidable ante to participating productively in society.

As urban living has undergone a renaissance in the past two decades, that political pushback has become surmountable in those places in America where speed is, in fact, not necessary to live a productive life. And there has emerged a strong constituency for the kinds of moves Oslo has taken to pursue a goal of no road deaths. (Witness, for example, San Francisco's recent decision to fully ban private cars from Market Street, or Manhattan's implementation of congestion pricing. And even much less dense, transit-friendly downtowns are rolling out things like protected bike lanes at a record pace.)

In the suburbs, though—or in younger U.S. cities where even the core is much more car-oriented—it's a different question. The idea of only slow travel remains unimaginable, and so Vision Zero seems unimaginable. The vast majority of places built after about 1970 (arguably more like 1945, but let's be charitable) cease to function, in their current configuration, if you can only drive 20 miles per hour.

Bike infrastructure has been a priority in Oslo. (via Flickr)

Changing that basic fact is our challenge. It’s possible, but it's going to require both institutional and far-reaching cultural changes, including but not limited to:

An emphasis on allowing (and rebuilding) complete neighborhoods where you can meet many needs within a 15-minute walk, and cars (where they’re present) move slowly and defer to people on foot.

Connecting those complete communities to each other by high-speed roads and/or public transit.

Creating alternatives to driving, and unlocking the strength in numbers that pedestrians enjoy when walking is a mainstream activity (29% of Oslo residents walk to work, just shy of the 34% who drive).

Recognizing that bike and pedestrian infrastructure comprises many of the highest-returning investments a local government can make.

Traffic calming to turn stroads into slow, safe urban streets.

Eliminate things like free parking in busy areas, which induces extra car trips.

Enforcement where needed to deal with the minority of true scofflaw speeders. (Oslo has markedly strict penalties for reckless driving.)

It's a holistic strategy. It will take decades. The lesson from Oslo is that if we embark on this path, the potential rewards are great. We too could have cities where nobody fears losing their son or daughter or parent or best friend to a car crash.

(Cover photo by 350.org via Flickr)

Daniel Herriges has been a regular contributor to Strong Towns since 2015 and is a founding member of the Strong Towns movement. He is the co-author of Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis, with Charles Marohn. Daniel now works as the Policy Director at the Parking Reform Network, an organization which seeks to accelerate the reform of harmful parking policies by educating the public about these policies and serving as a connecting hub for advocates and policy makers. Daniel’s work reflects a lifelong fascination with cities and how they work. When he’s not perusing maps (for work or pleasure), he can be found exploring out-of-the-way neighborhoods on foot or bicycle. Daniel has lived in Northern California and Southwest Florida, and he now resides back in his hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota, along with his wife and two children. Daniel has a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Minnesota.