Madison, WI, Is Lowering Traffic Deaths—But There’s Still Work To Do

Madison Bike Week 2022, with Mayor Rhodes-Conway (left) and Director of Transportation Tom Lynch (right). (Source: Madison Bikes.)

Political and engineering leaders in Madison, Wisconsin, are working to make their city streets safer by developing a culture of safety with the efforts of their Vision Zero initiative. As Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway said: “In Madison, we are committed to creating an environment where the community feels safe on our streets when walking, biking, taking transit or driving to work, school or wherever they may need to go. Working together with the community, we will build a positive safety culture and improve our design and construction processes to ensure that our streets are accessible for all people regardless of their age, ability, gender, race or method of travel.”

Madison’s preliminary efforts to create safer streets seem to be working, as the Transportation Commission released an update announcing that, “Following a 19% spike in 2020, fatalities and serious injuries on Madison roadways declined by 17% in 2021 and by a further 13% in 2022. There were 90 fatalities and serious injuries in the City of Madison in 2022, which is even lower than the pre-pandemic 2019 number of 106 (as reported by Channel 3000).”

To create safer streets in Madison, efforts have included a mix of lowering speed limits, using crash data to determine where to implement speed bumps or other small projects, and redesigning streets to promote safer travel for people walking and biking.

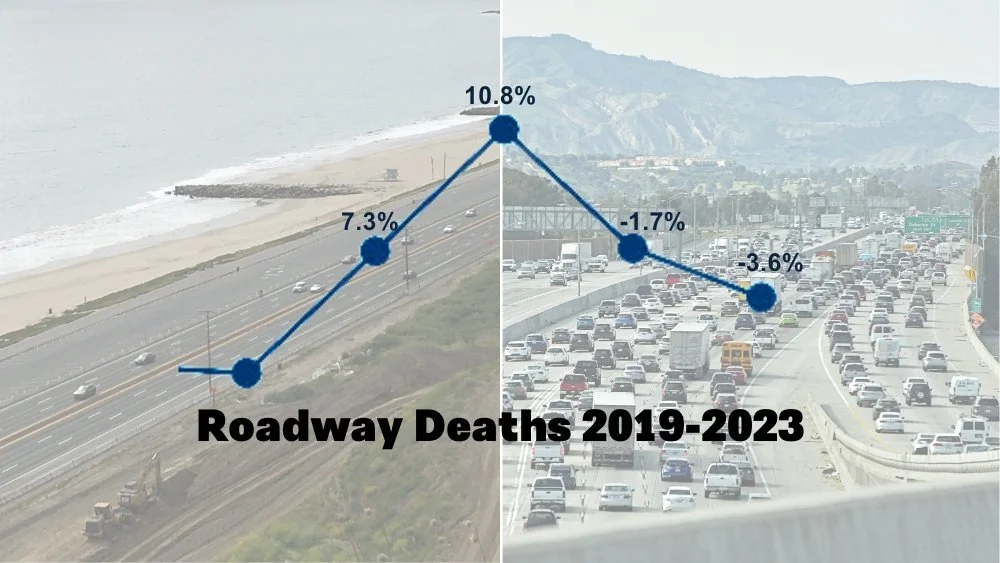

“I'm cautiously optimistic that actually, there is progress,” said Harald Kliems, president of the advocacy organization Madison Bikes. “Maybe there will be years when the numbers will not look so good.” Many cities throughout the U.S. have adopted Vision Zero—explicitly targeting zero traffic deaths as a goal—but in practice this often takes the form of media campaigns, rather than concerted steps to create a place through design where walking, biking, and driving is actually safe. “But if you compare what we see in Madison to what we see in other places. I think that comparison is definitely favorable … even if we keep the number relatively steady, then that's already better than what we see in other places.”

(Source: Madison Bikes.)

“I think [Vision Zero] has been really powerful in changing the conversation,” said Kliems. “And yeah, we've seen some early results. I mean, you can always read the numbers in multiple ways, but I feel that there probably has been some real progress even in the short time period. So hopefully, that will continue.”

This “culture of safety” has helped leaders in Madison develop a clear goal when addressing street designs: safety being their highest priority. It’s helped push forward design projects that local advocacy groups have been asking for, even before the city adopted a mindset of creating safe streets. “Madison is really good about whenever it goes in for a new road construction or has to repave the road or work on the utilities beneath the road, it always redesigns the road,” said Chris McCahill, who serves on the city’s transportation commission and its transportation policy and planning board. “So now every time there's a repaving project, we take the opportunity to say ‘Should something be narrower? Should there be bike lanes? Should there be sidewalks?’ And [we] work that into the repaving and reconstruction process.’”

One such redesign project, officially started because of a need to repave the street, sits along Atwood Avenue, where the City of Madison Engineering Division will expand the sidewalk by seven feet and include a separated bike lane.

During the early years of COVID, Madison closed down one lane of Atwood Avenue to create a temporary protected bike lane. Now the street will be permanently reconstructed with safe bike and walking facilities. (Source: Madison Bikes/Harald Kliems.)

“This project started before Vision Zero was actually on the radar,” said Kliems. “And so in a way, it's not a Vision Zero Project in itself, but the fact that it turned out the way that it did, rather than just repave it and basically rebuild the road as it is right now. I think that is the result of advocacy and is the result of the political situation.”

Another street that has been debated over how to make it safer is East Washington Avenue, which is known for its deadly design consisting of high-speed traffic and high volumes of people walking and biking. “It is one of the more dangerous streets in town,” said McCahill. The street, which is also a state highway, received lower speed limits, but has yet to receive any official plans for redesign due to the complicated logistics of working with the state department of transportation (WisDOT).

Safe Streets rally in response to a string of traffic deaths on East Washington Avenue. (Source: Madison Bikes.)

“Lowering the speed limit [on East Washington Avenue], we’re seeing that hasn’t been as effective,” District 6 Alder Brian Benford told Channel 3000 in 2021. “You throw in traffic enforcement, but our police resources are so limited at this point. The only thing that’s really going to alleviate this problem is we have to redesign East Washington Avenue. That’s going to require cooperation with the state DOT.”

The city may have a pathway to collaborate with WisDOT on a new street design through plans for a new bus rapid transit route, which is part of the effort to provide alternative options for people to access jobs and other necessities. “There are still some conversations happening between the city and the state about the potential to narrow that road or commit lanes entirely to the buses at certain times of the day,” said McCahill. “That's still a conversation that's happening.” According to the city’s bus rapid transit construction plans, the project seems most likely to turn the left lanes into bus lanes.

Even after a successful first two years of lowering traffic deaths and serious injuries, and redesign projects underway, the Transportation Commission notes in their Vision Zero update that they “still have a lot of work to do” to bring traffic fatalities and serious injuries down to zero.

“One of the powerful things about Vision Zero is that it's a very clear goal,” said Kliems. “And nobody really disagrees with that goal. Some people, if you ask them, ‘Should we have more bike lanes?’ then they might be like, ‘Well, maybe, unless that impacts parking.’ But if you ask people, ‘Is it acceptable that people die and get injured in traffic?’ almost everybody will say, ‘No, that's not acceptable,’ and therefore we’ve got to do something about that.”

In light of their safe streets efforts, the city of Madison has also received more than a quarter-million dollars in federal funds to help in its focus to eliminate traffic deaths and fund projects for better walkability and bikeability.

Dr. Jonathan Gingrich is a professor of engineering at Dordt College in Iowa. Unsatisfied with the standard materials for his transportation engineering class, he incorporated safe street design, including having his class conduct a Crash Analysis Studio. He joins today’s episode to talk about how he did this and the benefits it had for his students. (Transcript included.)