$4.7 Billion New Jersey Turnpike Expansion Ignores Local Leaders and Invites More Gridlock

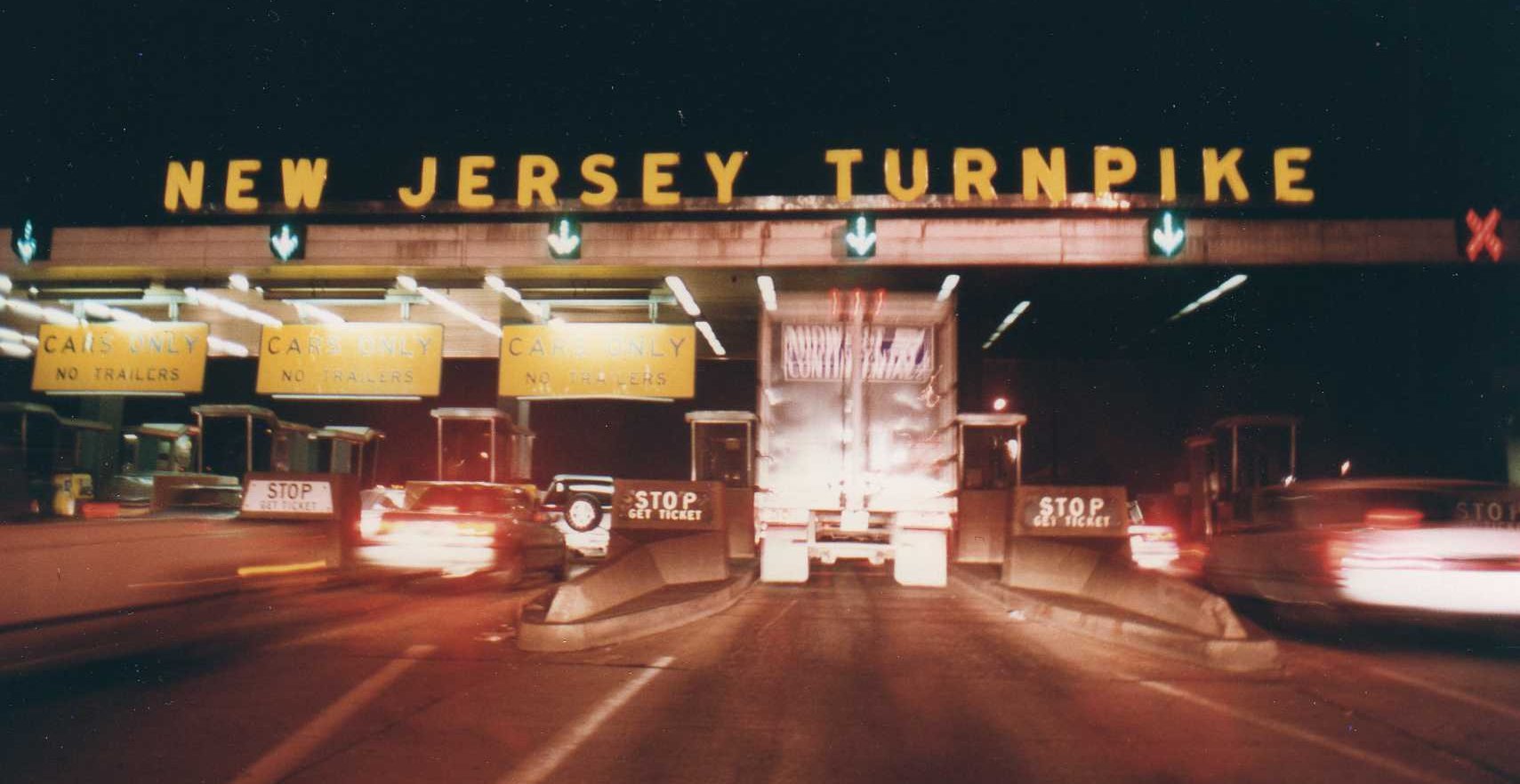

(Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

The New Jersey Turnpike Authority plans to spend $4.7 billion updating and widening an eight-mile section of the turnpike, which winds through some of the most densely populated regions in the state (Bayonne, Jersey City, and Hoboken) before leading into the Holland tunnel to Manhattan. Unsurprisingly, the turnpike is perpetually congested.

This project, however, will not relieve congestion. Instead, it merely diverts precious resources away from the maintenance of New Jersey’s existing transportation infrastructure toward the fruitless goal of funneling yet more motor vehicles through one of the most densely populated regions of North America.

The project has the support of Governor Murphy and the regional transportation organization (the NJTPA) but is opposed by several local leaders, including the mayor of Jersey City and Hoboken City Council.

The rationale for expanding the Jersey Turnpike will likely sound familiar to you: Congestion is wasteful and frustrating and if we don’t act, gridlock will worsen. Claims like these are often backed up with data about population growth, claims that the highway is crumbling and needs to be replaced anyway, and concerns about stifling the regional economy.

Yet adding lanes to the New Jersey Turnpike will not solve congestion. For over a century, planners, policy-makers, and engineers have tried this approach and time and time again, congestion reappears.

This phenomenon is known as induced demand, a term familiar to many Strong Town readers. Before the new lanes, some drivers avoided the congested roadway by driving on different routes, driving at different times of day, or walking, biking, or riding transit instead. Immediately after the new lanes are added, drivers can initially travel at higher speeds, but the faster speeds attract drivers who previously avoided the area due to congestion. Soon, the roadway is just as congested as it was before.

To make matters worse, induced demand is not simply about shifting trips from one location to another. Rather, road widening appears to lead to entirely new travel. We estimate that expanding the New Jersey Turnpike will result in at least an additional 100,000 vehicle miles traveled in the region each day. Our estimates are based on the SHIFT Calculator developed by the Rocky Mountain Institute. This calculator is based on decades of research on past highway projects and on a similar tool developed for California by Jamey Volker and Susan Handy. This easy-to-use tool allows anyone to estimate induced travel for any road project in the country.

All of the additional car travel has serious consequences. The air quality in the region already earns an “F” from the American Lung Association and nearby residents will suffer the health impacts from even worse air pollution caused by this project. The project will also undermine New Jersey’s climate change goals because more cars will mean more greenhouse gasses (GHG). Transportation is the number one source of GHG across the country and accounts for 42% of GHG emissions in New Jersey.

If New Jersey policymakers are serious about tackling congestion on the turnpike, they should explore the only option that is known to work: congestion pricing. One approach, which New York City is now pursuing, is area-based congestion pricing, where drivers pay a fee to enter the city center. The toll dissuades some drivers from entering the area by car, which reduces congestion. London, Singapore, and Stockholm have been using area-based congestion changing programs for decades.

A second type of congestion pricing is more appropriate for the turnpike: charging a dynamic toll to enter the freeway. Here’s how it works: as the road gets more crowded, the price goes up. A small number of drivers quickly adjust to the price signal by changing when, where, and how they travel. Just a few drivers need to leave the roadway to ease congestion. Not only do drivers enjoy higher speeds, more drivers get through the lanes. It’s a win-win.

Implementing dynamic tolls on the turnpike would be relatively straightforward, since the road is already tolled (the average turnpike trip costs $3.50). Calls for increased tolls or dynamic pricing are often met with reasonable concerns about the potential impacts on lower-income drivers. Luckily, there are plenty of ways to mitigate the effects of the additional costs. Policy-makers can distribute some of the toll revenues to low-income folks to use if and when they want to drive on the now uncongested roadway.

Thinking critically about the proposed Turnpike expansion is important because the same mistakes are being repeated across the country. Several states—including Oregon, Colorado, Texas, and California—are moving forward on multibillion-dollar highway expansions in and around major cities. In many cases, these proposals are opposed by small grassroots groups like Turnpike Trap in New Jersey or the youth-led group No More Freeways in Portland, Oregon.

These opposition groups are not just working against the DOT, they are also working to update longstanding but inaccurate conventional wisdom. When surveyed, almost two-thirds (64%) of American adults hold the incorrect view that roadway widening is likely to reduce congestion in the long-term. Understandably, people who misunderstand this fact are far more supportive of widening roads to fight congestion. The good news is that when members of the public learn about induced demand, many of them become less supportive of road widening.

To bolster ongoing opposition campaigns, it is essential to tackle the conventional wisdom head on. Grassroots advocates must communicate clearly and repeatedly why it is that widening the roadway simply won’t work to ease congestion. When the tide of public opinion turns, local leaders oppose projects.

There are promising signs of progress that the old conventional wisdom is losing ground. In opposing the New Jersey Turnpike expansion, local political leaders raised concerns about induced demand. In a formal letter opposing the project, the Mayor of Jersey City raised concerns that “additional traffic will be induced to enter Jersey City” and explained that congestion relief was “likely to be short-term and localized.” A resolution passed by the Hoboken City Council echoed these sentiments. The resolution noted that roadway widenings would leave roads “as congested as they were before.”

Strong Towns readers can help bring about this shift in conventional wisdom. The era of relentlessly widening freeways needs to come to a close.

Kelcie Ralph is an associate professor at the Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. In her research, Dr. Ralph works to identify and correct common misconceptions about travel behavior and safety to improve transportation planning outcomes.

Nicholas J. Klein is the director of undergraduate studies and assistant professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning in the College of Architecture, Art, and Planning at Cornell University. His research focuses on transport policy and the role of transportation in social and economic mobility.