How To Get Your Fire Department on Board With Narrowing Streets

When Jersey City swept headlines in 2022 for achieving zero traffic deaths on city streets, advocates across the country wondered: how? How was the city about to navigate the bureaucracy that notoriously delays street improvements? How was the city able to ensure community buy-in? And perhaps the most common question that arose was: How was Jersey City able to navigate resistance from emergency services?

Emergency services are a vital component of city safety. Yet, traffic calming—efforts to slow down cars by narrowing streets or introducing design elements that create friction—often meet with opposition from those services.

In Peekskill, New York, pedestrianizing Esther Street, a small alleyway flanked by local businesses, made the local fire department anxious. The nail in the coffin for Baltimore’s bike lanes was allegedly insufficient clearance for first responders, something advocates saw as a cop out. Even Celebration, Florida, a 10-square-mile New Urbanist experiment on the edge of Disney World, struggled to see eye-to-eye with its local fire department. The latter was considering removing many of the trees that shade Celebration’s streets.

Celebration, FL.

Jersey City ran into the same challenges. What sets it apart is how it navigated that resistance. “Those agencies are going to have to see it and feel it in practice,” Barkha Patel, the city’s director of infrastructure, told attendees of a recent Strong Towns event. “A conversation alone will never work.”

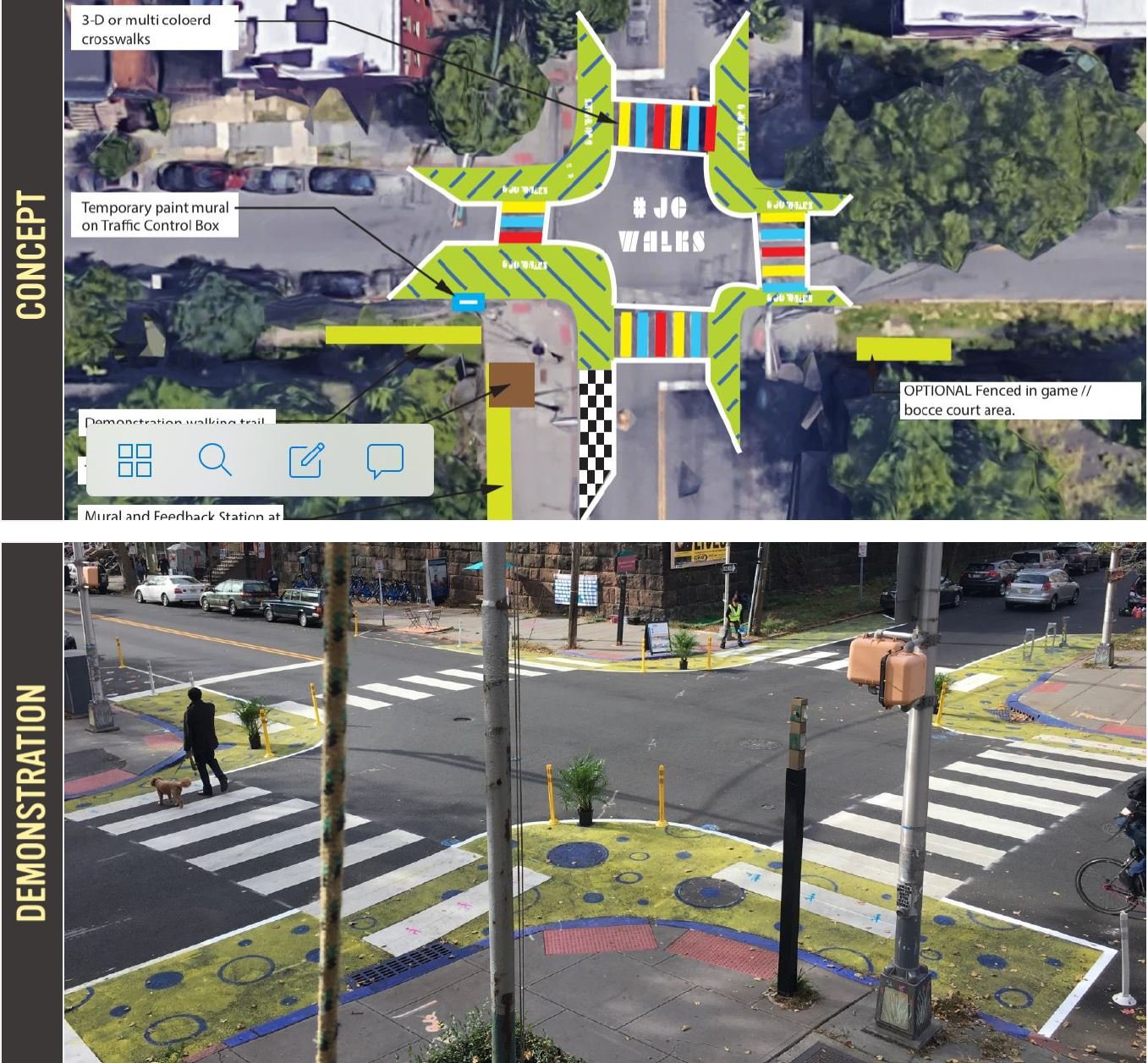

Patel described how the city would erect short-term installations—”for as little as six hours”—and invite first responders to maneuver the simulation. Sometimes these installations would take place on city streets and other times in municipal parking lots, something she notes any city could replicate. Most importantly, the mindset was one of cooperation, not compromise. That meant being receptive to feedback from first responders and being willing to make adjustments along the way.

A fire truck maneuvering the curb extension with city engineers on site to ensure the radii are appropriate. (Source: Jersey City.)

The same holds for the city’s many other placemaking interventions. “When we launched our parklet program, there were concerns that these new things in the street would be unsafe, no one would use them, etc.” Patel added. “In that case, it was important to not only spend time with the crew during the build and troubleshoot issues together but also to sit, socialize, and have coffee with them so they can see this new and unusual infrastructure being used in the way that it was intended for the public.”

Jersey City’s Director of Infrastructure, Barkha Patel sits and talks with crews during the installation of a parklet. (Source: Jersey City.)

Involving city agencies on the ground floor of the city’s plans has been indispensable to the city’s Vision Zero strategy. When the mayor formalized the city’s commitment to Vision Zero via executive order, Patel and fellow in-house Vision Zero champions carved out time for one-on-one discussions with city agencies and staff. “This included everything from talking through difficulties about their existing operations, budgets, etc. to helping them come up with feasible actions within their own agency that would contribute to the overall goal,” she explained.

By frontloading that effort, the city was able to set a tone of co-creation rather than antagonism. Coupled with very temporary installations, the city figured out an inexpensive yet productive way to nurture buy-in not only from emergency services but also the broader community. The dramatic decrease in traffic-related injuries and deaths show that the effort was well worth it.

RELATED STORIES

#BlackFridayParking

Even during the busiest shopping season, we have too much parking. It's time to get rid of the regulations that make it so.

Asia (pronounced “ah-sha”) Mieleszko serves as a Staff Writer for Strong Towns. A dilettante urbanist since adolescence, she's excited to convert a lifetime of ad-hoc volunteerism into a career. Her unconventional background includes directing a Ukrainian folk choir, pioneering synaesthetic performances, photographing festivals, designing websites, teaching, and ghostwriting. She can be found wherever Wi-Fi is reliable, typically along Amtrak's Northeast Corridor.