The Growth Ponzi Scheme Revisited: Houston as a Case Study

This article is part of a series on city finances. Read the first part here: “Introducing the Strong Towns Finance Decoder”

In 2016, we updated the original Growth Ponzi Scheme article to explain how cities across North America were financially imploding—not because of a lack of growth, but because of growth itself. To experience growth, cities are encouraged to take on enormous long-term liabilities to fund short-term expansions. This fiscally unsustainable pattern eventually leads to insolvency. We are three generations into this economic experiment and, as the numbers show, the system is breaking.

Few cities illustrate the consequences of this pattern as vividly as Houston, Texas. Houston has long been lauded as a pro-growth, free-market success story, a place where development happens fast, infrastructure keeps up with demand, and regulations don’t stand in the way of progress.

But underneath that reputation lies an enormous fiscal hole. Last year, Houston Mayor John Whitmire declared that the city is “broke,” citing a $160 million deficit. That’s a big number, but it barely scratches the surface of Houston’s real financial predicament.

The Growth Ponzi Scheme: A Recap

For decades, cities have chased growth as a way to generate prosperity. The premise is simple: build new infrastructure—roads, sewer systems, water lines—and let development follow. The rarely-questioned hope is that the tax revenue from new growth will be enough to cover both the initial investment and future service and maintenance. In the short term, this often appears to work. A city receives development fees, increases its tax base, and sees visible progress.

But underneath the surface, a dangerous financial pattern emerges. The cost of maintaining infrastructure doesn’t go away after construction—it only grows over time. Decades later, when pipes need replacing, roads need resurfacing, and public buildings need repairs, the original development fees are long gone, and the ongoing tax revenue isn’t enough to keep up. Cities then face a choice: raise taxes, take on debt, or chase even more growth to generate new revenue.

Of those three options, the most culturally palatable choice is growth—more of what seemed to be working—which only perpetuates the cycle.

This is the Growth Ponzi Scheme: cities take on long-term liabilities that vastly exceed the short-term revenue they generate. It’s a strategy that works only so long as the city keeps expanding at exponential rates, much like a financial Ponzi scheme that collapses when new investments dry up.

And now, in cities across the country, the bills are due and the fiscal stress is undeniable. This is especially true for a high-growth economy like Houston.

Houston: The Growth Ponzi Scheme on Overdrive

Nowhere is the Growth Ponzi Scheme more evident than in Houston. The city has grown from 600,000 at the end of World War II to 2.3 million today. In 1950, Houston was 113 square miles; today it is 640 square miles. In other words, they have grown their population by 380% by growing their land area by 570%.

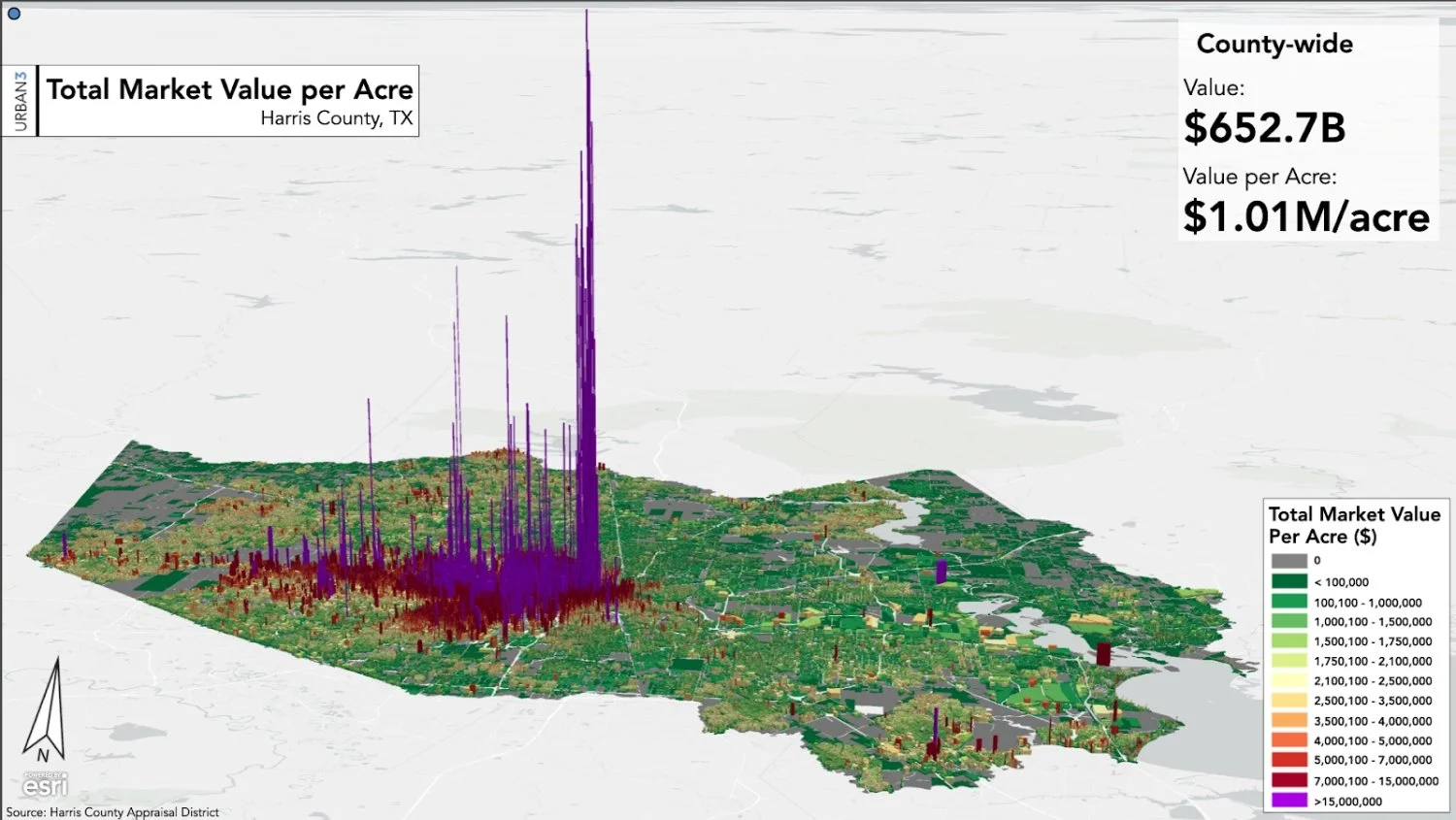

The city’s explosive growth was accomplished through annexation, developer-driven expansion, and public infrastructure investments meant to accommodate continued outward expansion. Each of these outward leaps costs more than the last and provides a tax base that is, in comparison, less financially productive. As shown by the fiscal mapping geniuses at Urban3, Houston has the troubling value-per-acre characteristics of a typical North American city, albeit at a larger scale.

The signs of fiscal stress in Houston aren’t new. In recent years, the city has struggled to balance its budget, resorting to short-term fixes like using one-time federal pandemic relief funds, delaying critical infrastructure maintenance, and meeting current obligations with increasing debt. Public services, particularly road maintenance and drainage systems, have suffered as the city prioritizes new development over upkeep. Meanwhile, the burden of past spending is growing—liabilities that must be covered by future revenue.

Mayor Whitmire’s declaration that Houston is broke wasn’t just political rhetoric. It was an admission that the city is reaching the point where new growth can no longer cover the costs of past obligations. With mounting debt, a shrinking window to delay necessary infrastructure spending, and a budget reliant on unpredictable external funding, Houston has become the latest—and perhaps most striking—example of the Growth Ponzi Scheme in action.

The Fiscal Health of Houston: A Structural Decline

To fully grasp Houston’s financial reality, we used the Finance Decoder to apply a framework that evaluates sustainability, flexibility, and vulnerability. What we found was a city whose financial position has been deteriorating for decades, obscured only by its continued outward growth and short-term fiscal band-aids.

A city’s fiscal sustainability is determined by its ability to provide essential services without continuously raising taxes or taking on new debt. One key indicator the Finance Decoder emphasizes is Net Financial Position, which measures whether past spending has left a surplus or a deficit that future taxpayers must cover.

Houston’s Net Financial Position is deeply negative—$14.6 billion in 2024—meaning that the city has already spent billions more than it can afford and is relying on future revenue to fill the gap.

That $160 million deficit they are struggling with today? If Houston can somehow stop making their Net Financial Position worse each year—which would be a radical departure from the trend—they can get back to a positive position by addressing that $160 million deficit every year for the next 94 years. In other words, this situation is not going to get better without structural changes.

Another metric of fiscal sustainability in the assessment—Total Assets-to-Total Liabilities—affirms the dire outlook. This indicator shows the value of all the city’s assets (including infrastructure), instead of just their financial assets, in comparison to liabilities. As a ratio, it shows the extent to which the city’s operations are generating a surplus (positive slope) or being financed with debt (negative slope). A ratio above 1 indicates solvency (more total assets than liabilities) while a ratio below one indicates insolvency (more total liabilities than assets).

Houston’s Total Assets-to-Total Liabilities has been in decline for over a decade, reaching a low point in 2016 when the city was insolvent (more liabilities than assets, by their own numbers). They appear to have recovered since then—there has been some improvement—but that recovery only looks good in comparison to the terrible financial position Houston has been in for decades now. Here’s how Houston’s Total Assets-to-Total Liabilities compares to Kansas City’s, which we looked at last week (and is really bad).

Kansas City is trending to insolvent. Houston is perpetually floating just above it.

Which begs the question: How likely is the upward trend away from insolvency likely to continue? The answer: Not likely. The Finance Decoder clearly shows where the improvements of the past few years have come from. They are all sources that are unlikely to continue or have painful consequences.

The first is government transfer payments. In 2020, Houston—like nearly all American cities—was given an infusion of relief money from the federal government. Houston’s Government Transfers-to-Total Revenues ratio shows that revenue spike and the subsequent declining trend as pandemic relief subsides. Houston now faces the reality that it has no permanent revenue stream to replace that money, let alone the base 10% of its budget it was getting in aid prior to the pandemic.

The second source of recent fiscal improvements is from lower interest rates. As Houston has been accumulating liabilities, interest rates have reached historically low levels and reduced the share of the budget dedicated to paying interest. From the assessment, here is Net Debt-to-Total Revenues (left axis) overlaid with Interest-to-Total Revenues (right axis).

Over the past decade, Houston has been able to roll over its debts to capture more favorable financing terms, a popular budget balancing trick. That trick only works, however, when rates are falling. Now that interest rates have moved up, and are likely to remain elevated for the foreseeable future, not only is refinancing at lower rates not possible, future debt—which Houston is structurally committed to—is going to be financed at much higher rates. This is going to put a lot of pressure on the budget.

The third thing Houston has done to make ends meet—and they’ve been doing this for decades—is deferring maintenance on their core infrastructure systems. The Finance Decoder looks at Net Book Value-to-Cost of Tangible Capital Assets, which roughly tracks how well a city is maintaining its physical infrastructure. Houston is falling behind in this area as well.

The remaining useful life of its infrastructure has declined from 67% in 2005 to just 56% in 2024, a sign that the city is not keeping pace with its maintenance obligations. Every year that maintenance is deferred, repair costs increase, pushing Houston further into financial distress. And because of its development pattern, Houston has a lot of infrastructure to maintain, way more than their tax base can support.

A City on the Brink

Houston’s financial trajectory is unsustainable. The city is caught in a cycle where past obligations dictate future spending, where every budget cycle becomes an exercise in postponing fiscal reckoning. The Growth Ponzi Scheme is not just a theory—it’s playing out in real time in one of America’s largest cities.

Other cities should take note: Houston’s crisis is not unique. It is simply further along the path that many municipalities are on. The key to avoiding this fate is to rethink our pattern of development, prioritize financial sustainability, and make hard choices now—before insolvency forces them upon us.

If you are a city leader, planner, or concerned citizen, the time to act is now. The Strong Towns Finance Decoder provides a framework for understanding your city's financial position and making informed choices before crisis strikes. The question is not whether your city will face these challenges, but when. The sooner communities confront these issues, the better prepared they will be to build a financially resilient future.

We used data from Houston’s annual financial reports to prepare this analysis. You can see how we did that in this Google Sheet. In the coming weeks, we will release a version of this spreadsheet, along with instructions, for you to do your own assessments. Sign up here to be alerted when that package is ready.

Read the next part of this series: “Cities Are Not Nations: The Hard Budget Reality of Brainerd, Minnesota”

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.