Cities Are Not Nations: The Hard Budget Reality of Brainerd, Minnesota

This article is part of a series on city finances. Here’s what we’ve covered so far:

In economic debates, it’s common to hear that a government’s budget is nothing like a family’s budget. Some prominent economic thinkers argue that using household finances as an analogy for government spending is misguided—after all, national governments can print money, borrow indefinitely, and manage debt at an entirely different scale.

This argument might hold for sovereign nations, but it completely breaks down when applied to cities. Cities, unlike national governments, cannot create money, borrow without limit, or endlessly defer liabilities without consequences. These distinctions are not minor, but they are often overlooked in our cultural discourse.

A city’s financial reality is much closer to that of a family than it is to a federal government. When a family overspends, it has to make tough choices—cutting back on expenses, taking on debt (making an obligation against future income), or finding new income sources to cover the shortfall.

If a city overspends, it also has limited options: raise taxes, cut services, take on debt, or default on its obligations to creditors or—more commonly—to the residents it serves. Particularly in a small town where there is much less slack in the system, financial choices are immediate, tangible, and often painful. This is especially true for a small city like my hometown of Brainerd, Minnesota.

Using the Strong Towns Finance Decoder, we can see exactly how Brainerd’s financial constraints illustrate the stark difference between municipal and national budgeting. This is the third article in our series on local government finance. It builds on the Finance Decoder that we previously used to analyze Kansas City and Houston.

The Budgetary Constraints of a City

A city government, like a household, must live within its means over the long term. Unlike some federal governments, a city has no central bank to monetize debt and no ability to run endless deficits. Every road built, every pipe laid, and every city service provided comes with an obligation—one that must be met with real money collected from real people.

Brainerd, a small city in central Minnesota, faces the same fundamental financial pressures as thousands of communities across North America. It has infrastructure to maintain, services to provide, and a limited tax base to fund everything. But its ability to manage long-term obligations is constrained by its limited ability to delay financial reality.

To understand Brainerd’s financial condition, we turn to the Finance Decoder, which evaluates three key indicators—sustainability, flexibility, and vulnerability—to better understand the financial trends of Brainerd’s annual budget decisions.

1. Sustainability: Can Brainerd Afford What It Has Built?

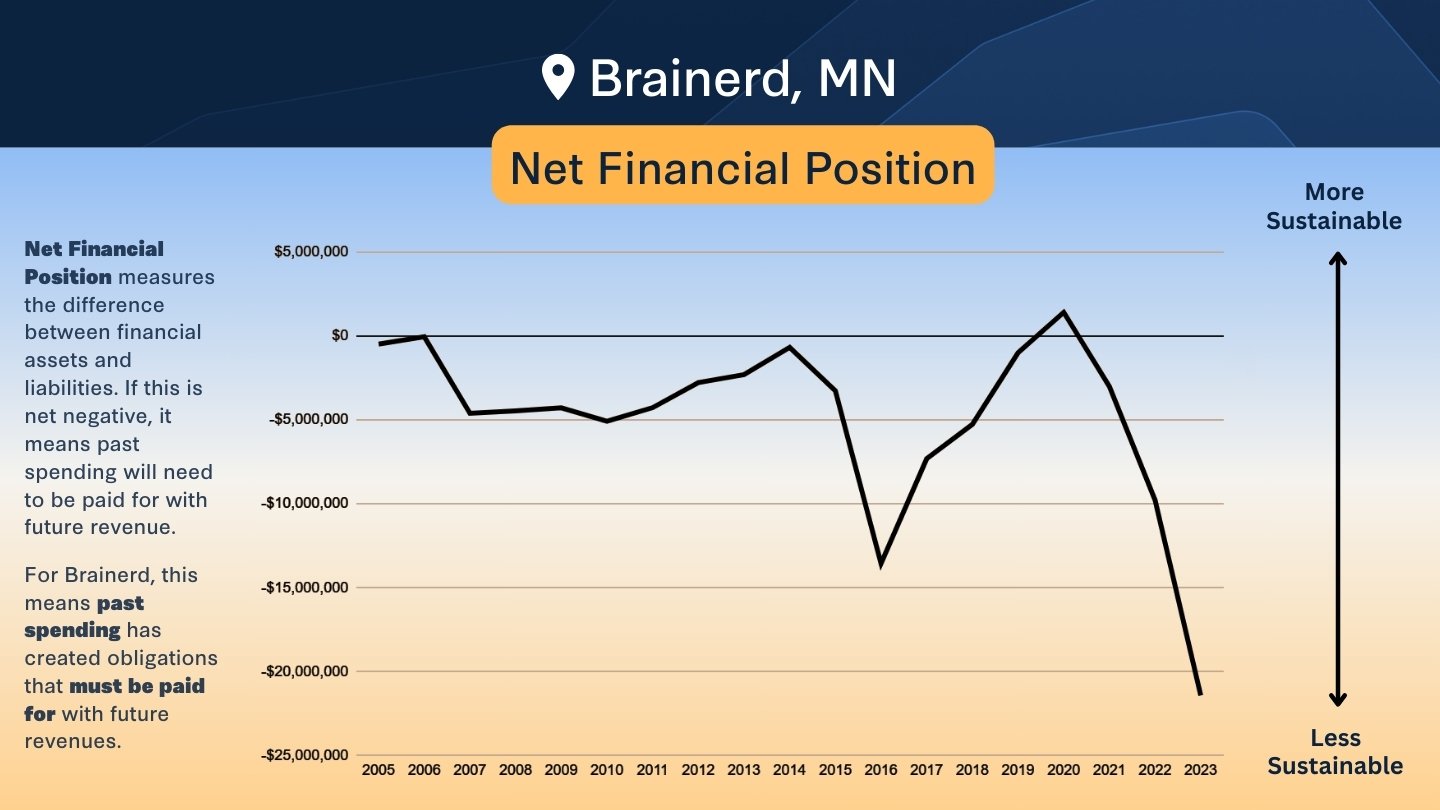

Brainerd’s Net Financial Position has more volatility than Kansas City or Houston, which is to be expected from a smaller system. The Net Financial Position is the culmination of all past budget surpluses and deficits; in Brainerd, there is a downward trend with a dramatic dropoff in the most recent few years. This means that the city’s past spending has created obligations that must be paid for with future revenues—over $21.4 million in past spending.

Brainerd is a small town, so its $21.4 million Net Financial Position may look quaint compared to Houston ($14.6 billion) or Kansas City ($3.7 billion). Yet, a big city can afford a lot more than a smaller city. The way to determine the level of burden is to compare each city’s liabilities in proportion to its overall capacity. The Finance Decoder does this by comparing Financial Assets to Total Liabilities, a restatement of the Net Financial Position (Financial Assets - Liabilities) as a ratio (Financial Assets / Liabilities). Here are those three cities in comparison.

With the exception of one year for Brainerd (2020), all three of these cities have accumulated liabilities in excess of their financial assets. All will need revenue increases or service cuts in the future to reconcile their cumulative deficit. While Brainerd’s situation is not nearly as dire as that of Kansas City or Houston, there is a lot more volatility in the small town’s budget. Said another way: In small towns, there is a lot less margin for error, especially when taking on large projects, large debts, and large liabilities.

Brainerd is technically still solvent—its own financial numbers show more total assets than liabilities—but the trendline in the Total Assets-to-Total Liabilities analysis paints a concerning picture. If Brainerd’s assets (roads, buildings, utilities, etc.) are not growing at the same rate as its liabilities (debt, pension obligations, deferred maintenance, etc.), the city is moving toward a future financial crisis. Like many small cities, Brainerd has had to make difficult choices—delaying street repairs, postponing building updates, and hoping that revenues will eventually catch up with expenses.

An even starker reality is reflected in Net Debt-to-Total Revenues, which measures the size of Brainerd’s liabilities relative to the income it generates. A rising ratio means that a growing share of future revenue is already spoken for—committed to repaying past obligations instead of funding current and future services. Brainerd’s Net Debt-to-Total Revenues has followed a problematic trend, climbing over time as promises accumulate faster than revenues grow.

The longer this trend continues, the more precarious the city’s position becomes. Over time, each new budget cycle will become more constrained as the ability to invest in community needs is eroded by financial obligations from the past. Without intervention, Brainerd’s leaders will find themselves increasingly boxed in, forced to either cut services, raise taxes, or continue down an unsustainable path of debt accumulation.

2. Flexibility: How Much Room Does Brainerd Have To Adapt?

Flexibility refers to how much financial maneuverability a city has when economic conditions change. One way to measure this is Interest-to-Total Revenues, which tracks how much of a city’s budget goes toward paying interest on debt. The higher this number grows, the more it limits the city’s ability to invest in new priorities.

Like most U.S. cities, Brainerd was able to borrow at rates that declined steadily over time since the 2008 financial crisis. As old debt at higher rates was replaced with new debt at lower rates, the amount of interest paid declined. Except for a spike in 2021/2022, the city seems to have the capacity to pay more in interest, which provides it some flexibility as it deals with its negative Net Financial Position in a rising-rate environment.

Some of that interest flexibility has been attained by the city neglecting its infrastructure. Net Book Value-to-Cost of Tangible Capital Assets shows whether a city is keeping up with infrastructure maintenance. In Brainerd’s case, the useful life of its assets has been steadily declining, from 68% useful life remaining in 2005 to 55% in 2023. This means roads, pipes, and public buildings are wearing out faster than the city has invested to repair or replace them.

3. Vulnerability: How Dependent Is Brainerd on Outside Support?

Small cities generally experience more budget volatility than larger cities. This volatility can increase when a city is reliant on outside sources of revenue, like state and federal aid, to balance its budget. The Government Transfers-to-Total Revenues portion of the assessment reveals the extent to which state and federal funding plays a role in balancing the city’s finances.

Brainerd, like many small cities, relies heavily on external funding sources to supplement its budget. While government transfers can help cities bridge financial gaps, they also create risk. If state or federal support is reduced, Brainerd has few options to make up the shortfall. This makes the city vulnerable to policy decisions beyond its control. Without sufficient local revenue generation, any reduction in external funding could force deep cuts to services or significant tax increases.

A City’s Budget vs. A Nation’s Budget

Brainerd’s financial position is not unique. Cities everywhere are facing the same harsh reality: They cannot operate like national governments. The popular economic argument that “governments are not like families” might apply at the federal level, but for cities, the comparison is entirely appropriate.

Cities, like families, must live within their means. They cannot simply “grow their way” out of financial distress if that growth is based on accumulating long-term obligations without a plan to sustain them.

If Brainerd defers road maintenance today, it doesn’t just disappear—it gets more expensive in the future. If Brainerd takes on more debt than it can afford, interest payments will squeeze future budgets. And if Brainerd counts on outside funding to balance its books, it is at the mercy of decisions made at higher levels of government.

Small-town budgets are inherently more volatile than those of larger municipalities, as they rely on a narrower tax base and fewer revenue streams. This means that the burden for fiscal prudence is even greater in these places—small cities like Brainerd must be even more careful in how they manage debt, plan infrastructure spending, and ensure financial resilience against economic downturns or shifts in state and federal funding.

I love this town. I believe the people who run it genuinely have the best intentions for its future. The challenges we face have been building for decades—this isn’t the result of one city council’s decisions or the actions of a few politicians, but rather a long-standing pattern of choices made over time. The purpose of the Finance Decoder is to help local leaders gain a clearer understanding of the city’s financial realities—to recognize trends they may not have seen before—so they can ask better questions and make more informed decisions for the future.

A Call to Action: Stronger Cities, Smarter Budgets

The Strong Towns Finance Decoder provides a framework for cities to take control of their financial future. The data from Brainerd is clear: Cities cannot act like national governments. They must be financially self-sufficient, plan for long-term obligations, and avoid the illusion that growth alone will solve their problems.

City leaders, planners, and residents must demand a more realistic, fiscally sustainable approach to municipal finance. That means prioritizing maintenance over expansion, ensuring that new development actually pays for itself, and making financial decisions with the same discipline that families must use in their own budgets.

The reality is simple: Cities must make hard choices today to avoid financial hardship tomorrow.

Find out where your city really stands financially. The Strong Towns Finance Decoder is available now for anyone to use. Sign up here and we'll send you the Decoder, along with additional resources to help you use it and share the results.

Read the next part of this series: “Cities Are Already Defaulting on Their Debts”

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.